In Bill Cotter’s beloved children’s book series, Don’t Push the Button! a mischievous monster named Larry presents young readers with a tantalizing big red button, sternly warning them not to press it. Of course, the allure proves too strong for toddlers, who gleefully ignore the advice, unleashing a cascade of silly chaos – turning Larry into a polka-dotted elephant or summoning a horde of dancing bananas. The books’ humor lies in the predictable disobedience, but the underlying lesson is clear: some temptations are simply too powerful to resist.

This whimsical analogy holds a sobering truth for the world of economics. Far too many economists, in their policy recommendations, unwittingly craft similar “big red buttons” for policymakers. They design sophisticated interventions intended to fix specific market imperfections with the caveat that these tools should be used judiciously – only when necessary, and with precision. Yet, politicians, driven by electoral pressures, find these buttons irresistible in off-label uses and abuses. The result? Not playful pandemonium, but real-world economic distortions such as deficits, inflation, and moral hazard that often exacerbate the very problems the policy was prescribed to solve.

Economists often position themselves as impartial social scientists, perched in ivory towers far removed from the messy arena of politics. They deploy intricate models to pinpoint “optimal” policy response. For instance, during a recession, they might calculate the exact multiplier effect of a fiscal stimulus package, advocating for targeted government spending to boost aggregate demand. Or they may recommend an “optimal” tax rate or an exactly tailored tariff that can generate slight efficiency gains under rare conditions. In monetary policy, they endorse tools like quantitative easing or financial bailouts to stabilize banking systems. These recommendations stem from a genuine desire to mitigate harm and promote efficiency, rooted in the observation that markets aren’t perfect: externalities, information asymmetries, and behavioral biases can lead to suboptimal outcomes.

However, by blessing these expansive toolkits, economists inadvertently empower policymakers with levers that beg to be pulled in ways and contexts well beyond what the economists intended. Even if the advice comes with implicit disclaimers, such as “use sparingly,” “monitor side effects,” or “phase out promptly,” these are as effective as Larry’s warnings to a curious child. Policymakers operate in a high-stakes environment where incentives skew toward action over restraint. Re-election hinges on visible results: cutting ribbons on pork-barrel infrastructure projects funded by stimulus or touting low unemployment figures propped up by easy money. Long-term consequences, like mounting public debt, systemic financial risk, or bubbles, are conveniently deferred to future administrations.

This oversight isn’t just a minor flaw; it’s a fundamental methodological error. As Nobel laureate James Buchanan, a pioneer of public choice theory, demonstrated, economists cannot claim scientific neutrality while ignoring the incentives of those who wield power. Public choice theory applies economic reasoning to politics, revealing that policymakers are not benevolent philosopher-kings but rational actors pursuing their own interests – votes, campaign contributions, and bureaucratic expansion. Buchanan critiqued the “romantic” view of government prevalent in much of mainstream economics, where market participants are assumed to be self-serving and prone to failure, while public officials, and the voters who elect them, are idealized as altruistic guardians of the public good.

Consider two historical examples. In Lombard Street, Walter Bagehot famously laid out the rules for central bankers to follow during a financial panic, necessary to prevent policymakers from pressing the monetary button inappropriate and generating moral hazard or disequilibrium. But, even after a century of model calibration and data refinement, even academic economists when serving as monetary authorities could not resist pushing the button. Politic incentives made actions that economists held to be inadvisable prior to their policy roles irresistible after they assumed their roles. With bailouts of the commercial paper, bond, main street lending markets, not to mention state and municipal governments, the Fed’s response to Financial Crisis and COVID-19 have demonstrated how incentive-incompatible these policy recommendations are in practice.

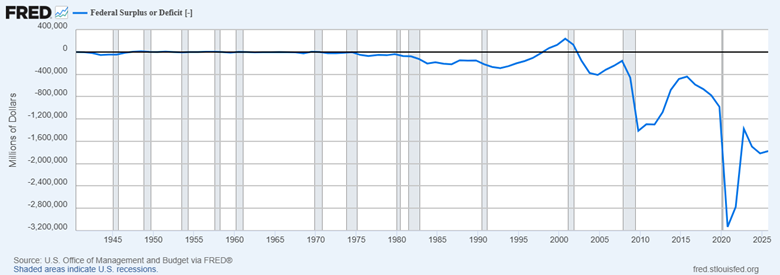

Countercyclical stimulus recommended by John Maynard Keynes to combat a recession has suffered a similar fate. While Keynes questioned the legitimacy of government spending more than 25% of national income, he nevertheless gave policymakers an excuse to disregard what James Buchanan and Richard Wagner called the “old-time fiscal religion” of balanced budgets. Politicians hit the button and now budget deficits are the norm.

To break this cycle, economists must integrate an analysis of incentives into their core framework. This means adopting a “constitutional economics” approach, as Buchanan advocated – one that designs institutions and policies with built-in safeguards against abuse. For instance, instead of open-ended stimulus authority, recommend automatic stabilizers like unemployment insurance tied to verifiable economic triggers, with sunset clauses to prevent mission creep. In monetary policy, advocate for rules-based frameworks, such as NGDP targeting with strict accountability, over discretionary interventions that invite political meddling. The tradeoff is less discretion and precision, but it is necessary to create institutions robust to real-world deviations away from idealized policymakers.

Moreover, economists should explicitly acknowledge the principal-agent problem in government: oftentimes uniformed and biased voters (principals) struggle to monitor policymakers (agents), leading to agency capture by special interests. By assuming away these dynamics, traditional policy advice becomes not just naive but unscientific, as Buchanan noted. True rigor demands modeling both market and government failures symmetrically. This means questioning not only why markets falter but why government interventions might amplify those failures through perverse incentives.In the end, the lesson from Don’t Push the Button! is timeless: if you don’t want chaos, don’t create the button in the first place. Economists would do well to heed it, crafting advice that anticipates real-world incentives rather than ideal scenarios. By doing so, they can foster more resilient economies, where markets handle what they do best, and government intervenes only when truly essential – and with safeguards on the buttons to keep them from being mashed indiscriminately.