In December 1934, The American Family Robinson came to the radio airwaves. The new show, like many of its competitors, featured a combination of mystery, family life, romance, drama, adventure, comedy, and intrigue. But it also had something unique to offer. Unlike other radio soap operas, The American Family Robinson openly celebrated free markets, private property, and self-reliance.

The American Family Robinson was part of a strategy by the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) to sway public opinion against the New Deal. Acting through a front group, the National Industrial Council, industry interests created a radio soap opera weaving together entertainment, promotion of entrepreneurship, and opposition to big government.

But the big networks showed no interest. NBC executives were typical in fearing that the series, though potentially profitable for the bottom line, might flout the mandate of the Federal Communications Commission to promote the “public interest, convenience, and necessity.” Network executives even banned local affiliates from carrying the show. “You would probably not find in the entire series any specific sentence that could be censored,” summarized a scriptwriter for NBC, “but the definite intention and implication of each episode is to conduct certain propaganda against the New Deal and all its work.”

The producers responded with a strategy to bypass the networks through syndication to local stations, a practice that was still quite rare. The National Industrial Council recruited local employers to fund transcription of the program onto 16-inch phonograph discs and mailed them to stations weekly or bi-weekly.

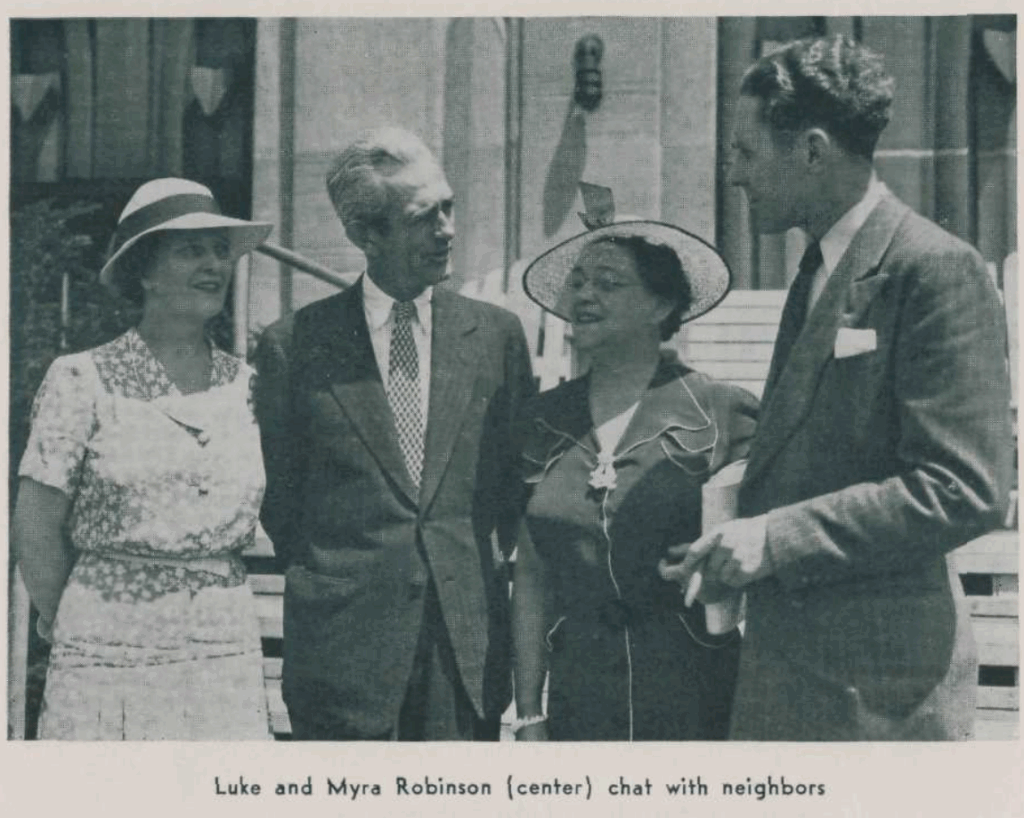

The American Family Robinson is set in the fictional town of Centerville. The main characters are Luke Robinson, who edits and publishes the town’s newspaper, the Centerville Herald; his wife Myra, who hosts her radio show, their daughter Betty, and Betty’s husband, star reporter Dick Collins. In nearly every episode, Luke good-naturedly and patiently explains (in a manner anticipating the sagacious Judge Hardy in the later hit movie series) the importance of thrift, low taxes, property rights, self-reliance, and limited government.

The production was helmed by professionals including Martha Atwell (a rare example of a female director) and the script-writing husband-and-wife team of Douglas Silver and Marjorie Bartlett Silver. The actors had extensive stage and radio experience. On the strength of the writing and characterizations, the show developed a significant fan base. Many tuned in for the intricate plots, including cliffhangers about murder and kidnapping, as much as for the ideas.

A particular favorite among listeners was William “Windy Bill” Winkle (played with aplomb by Shakespearean actor Joe Latham), Luke Robinson’s mooching brother-in-law and self-invited house guest. Originally intended to be an incidental character, he proved so popular that he became a cast regular. Windy often sparks humorous exchanges to underscore the show’s themes. He combines zealousness for socialism with an equal certainty in the brilliance of his get-rich-quick schemes. He also courts the wealthy (at least in his mind) Spinster Leticia Timmons, an entrepreneurial dress shop owner. “Look what happened to me,” Windy complains, “I’ve spent the best years of my life, trying to be an honest business man and what do I get for it? Nothing. That’s what! Take my patented Little Wonder adjustable hair cutting bowl for home use…but the barber trust and big business kept it off the market!” Brushing aside this theory of a big business conspiracy, Luke asks “Who are the big fellows anyway? They’re little fellows who worked hard enough under the same rules that apply to you and me, to become big fellows.”

Luke opines to Windy that “for a man who claims to oppose capitalism as much as you do, you’re going to an awful lot of trouble to be a capitalist yourself.”

He gets a quick response: “Quite simple my dear fellow. I advocate socialism for the good of all the people but for me personally, well, a fellow has to do the best he can for himself…If socialism ever comes to this benighted country I’ll be only too glad to share my property in return for a share in everybody else’s property”

Luke points out that under an equal division of wealth, this would amount to only forty-three dollars per person but Windy does not think this is a fatal flaw. At least, he points out, profit-centered businesspeople would no longer be calling the shots. Luke responds, “After a fairly long life of observation, I have failed to discover that politicians are more to be trusted than businessmen.”

To get rid of his annoying houseguest, Luke persuades his friend, Henry Jason, to hire Windy as a glorified office boy in his new factory, helping him become self-supporting. Jason agrees to humor Windy’s vanity by designating him as “Contact Manager.”

“That’s fine, it doesn’t mean a thing and it sounds important,” Jason observes, “but I don’t know whether one could ask a contact manager to go and get some stamps, for instance.”

“Oh, easy, just ask him to uh… contact the post office and bring some.”

Windy visits the factory construction site and proceeds to lecture the foreman about his job. After listening to his advice, the foreman vents: “That’s just the trouble. We got contact managers thinking they can build factories and professors running business and…smart-aleck lawyers trying to run the whole government. There’s only one thing those people can do to help business recovery and that’s the same thing a blacksmith would do if you took your watch to him to be repaired: he’d leave it alone.”

But Windy’s confidence in his worldview never flags. In answer to the charge that he is a “utopia chaser,” Windy emphasizes that he only wants to “devote my ingenuity to the betterment of my fellow men through careful research into the possibilities of a planned economic solution.” To this, Dick Collins answers, quite overoptimistically, that “by the time you get around to it you’ll be completely out of fashion. The passing of the theorist plague is already well underway. Where’s the technocracy of yesteryear, the EPIC [End Poverty in California] plan, the public pension plan, and all the other crackpot plans? They’re all wilted under the cold light of reason.”

Other memorable characters include the charmingly uncouth but down-to-earth ex-boxer Gus Olson. Gus knows all the “big shots” in town and is a rival with Windy Bill for Leticia’s affections. He works as little as possible and is proud of it. But Luke, impressed by his intelligence, bluntness, and resourcefulness, sees greater potential. As a kind of experiment, he hires him as a janitor with the title of “boondoggler.” Much later, Gus finds out that a distant Irish relative has willed him two million dollars.

The show’s defense of the “possessive instinct” anticipates the views of Ayn Rand.

Luke: I’ve just been thinking in here away from that maddening crowd that the possessive instinct is the most valuable one owned by man.

Myra: My, that sounds greedy.

Luke: No, far from it. The instinct to acquire possessions

to save them build on them is the greatest contributing

factor in the growth of civilization.

Myra: Well then, it’s lucky we’ve got a possessive instinct.

Luke: What I don’t understand is why our radical friends are intent on destroying that instinct. They seem to think the ideal existence would be to crush it to make way for a scheme of things that only includes the mass of dumb sheep accepting what the political overlords feel like handing down to them.

The central role of women in the writing and production was evident in several storylines. Myra Robinson, who hosts her own radio show in Centerville, and Betty Robinson Collins are instrumental in a campaign to save the Centerville Herald from almost inevitable bankruptcy. Gus does his best to help, volunteering that the dubious Butch Scarlotti, a “pal of mine…could loan us anything up to 100 grand and not even feel it.” Dick gently rejects the offer because any association with the likes of Scarlotti would damage the paper’s reputation. Finally, the group decides to approach Robinson’s factory-owning friend Dave Markham, but only after launching a successful campaign to increase circulation and sell ads.

It is Betty who comes up with the winning strategy. She notes that people are more likely to buy a paper, and purchase ads, if it includes stories about “their worst enemy or their best friend or, better yet, has their name in it.” Anticipating social media and user-generated media, the group supports creation of a “reader column” in which three readers per day air their views.

Dick Collins observes readers would not only subscribe to see themselves in print, but “then they’ll subscribe to compare their column with those written by their friends.” With Myra’s broadcasts spreading the word, he adds that “we could keep it going we would never run out of contributors or subscribers either, while we could go right through the town directory and then go back and start over.”

The success of the fundraising campaign leaves Windy unimpressed, however: “this one case of mutual aid doesn’t make a summer. Your precious businessmen are still storing away the profits. Why, it wasn’t Private Industry that pulled us through the depression. Everybody knows that it was federal funds that kept us going.”

To this, Dick notes that these “stored away” profits provided the necessary wherewithal for rescue efforts, such as the effort that saved the Herald. “The whole country,” he adds, “has been living on Capital accumulated during the good years.”

Changes in broader political and regulatory context shaped the eventual fate of The American Family Robinson. By the late 1930s, programs deemed too “controversial” (especially those questioning the New Deal consensus) were increasingly under attack.

The American Family Robinson was one program that suffered pressures from both the FCC and the “voluntary code” of the National Association of Broadcasters. The code prohibited stations from accepting “free offers” if the purpose was to recruit members for an organization or to foster a point of view.

“Unless the station presents the other side of the picture,” it warned, “it might be accused of bias.” In June 1939, the National Association of Broadcasters specified that both The American Family Robinson and the ACLU, which regularly sent out scripts to stations providing commentary from a civil liberties perspective, were on its list of potential offenders. It urged stations to “write to Headquarters for information about these.”

In response to accusations that The American Family Robinson was anti–New Deal, the National Industrial Council replied defensively that it was “not ‘anti-’ anything or anybody.” Rather the goal of the program was to “present openly, and as effectively and attractively as radio will permit, the fundamental principle that freedom of speech and of the press, freedom of religion, and freedom of enterprise are inseparable and must continue to be if the system of democratic government under which this country has flourished is to be preserved.”

By 1940, when the National Industrial Council produced a new run of shows, the content became ever more innocuous and often indistinguishable from a typical substandard soap opera. The previous eagerness of characters to question, or even discuss, the New Deal welfare and regulatory states gradually faded away. To the extent that the later episodes expressed ideas or broader social goals, they took the form of simplistic bromides on such topics as the importance of marital understanding and the need for concerted cooperation for national defense mobilization. Windy Bill, later played by a WC Fields wannabe who lacked Latham’s deft touch, became typical comedy relief, and nothing more.

Several factors contributed to these changes, including a shift in national priorities on the eve of war and pressures from the National Association of Broadcasters which made stations more averse to politically charged topics. The National Association of Manufacturers also had an ambiguous influence. To many in that organization, a defense of the parochial interests of big business (it had supported the extremely statist National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933) took precedence over promoting the free market as such. When the final episode signed off in September 1941, the show was only a shell of its former self.

The American Family Robinson was mostly forgotten in later years. Most historians of radio mention it only as a sidelight and, despite much ideological overlap, nobody has connected it to libertarian thinkers of the period such as Ayn Rand, Isabel Paterson, Rose Wilder Lane, or people who in turn influenced a later generation of thinkers like Milton Friedman and Murray Rothbard.

Probably the most intriguing historical link was between African-American novelist and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston (who had great affinity for libertarian ideas) and the two script writers, Douglas Silver and Marjorie Bartlett Silver. The Silvers (Douglas founded and was president of the main radio station in Fort Pierce, Florida) befriended Hurston during the 1950s. After Hurston had a stroke, Marjorie was instrumental in salvaging a copy of her biography of Herod the Great, which had narrowly escaped a bonfire.

During its heyday, The American Family Robinson registered an often creative, intelligent, and entertaining dissent from the New Deal consensus. The show’s exposition of the benefits of markets, self-reliance, voluntarism, and thrift, as well as the follies of bureaucracy, anticipated the later popularization of these ideas. But The American Family Robinson was also fighting against the current during a period when these ideas were on the defensive, and the welfare and warfare states were ascendant.