Ten Points

- Commercial nuclear fission dates from the 1950s, a time when electricity was generated by fossil fuels (80 percent) and hydro (20 percent). Today, nuclear supplies 19 percent of US generation and 10 percent globally. Nuclear fusion remains in the laboratory with little prospect of foreseeable commercialization.

- Nuclear power is a government-enabled industry. It emerged from wartime R&D and continued under the postwar “Atoms for Peace” subsidy programs. The Price–Anderson Act of 1957, which capped liability payouts from nuclear accidents, was instrumental.

- Rate-base treatment under state-level public utility regulation was a de facto insurance policy for utilities to commit to experimental technology. A “bandwagon effect” occurred after Westinghouse and General Electric offered performance (“turnkey”) guarantees for new reactors, but losses ended the program and transferred risk to owners and ratepayers.

- Government subsidies incited multiple technical designs and plant-size escalation in the 1960s, all contributing to cost and construction failures in the next decade.

- Activist regulation by the Atomic Energy Commission/Nuclear Regulatory Commission contributed to cost overruns and completion delays. Extensions of the Price-Anderson Act (1966, 1975, 1988, 2002, 2003, 2005, 2024) have kept federal regulators in charge.

- Orders for new reactors ended in 1979, the year of the Three Mile Island accident. In response, nuclear utilities engaged in collaborative best practices that have proven effective for safety and reliability.

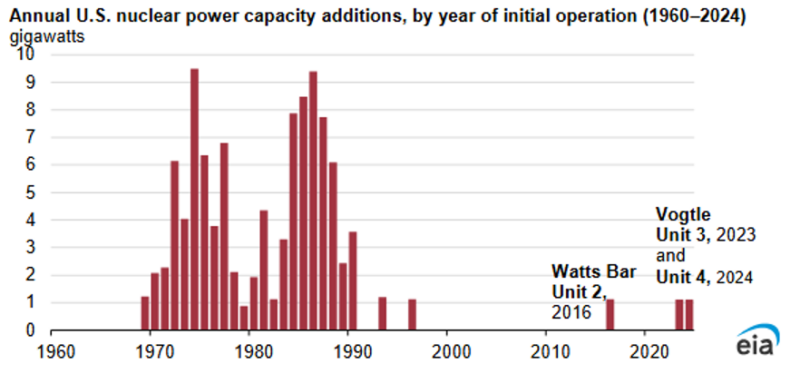

- New subsidies in the Energy Policy Act of 2005 resulted in four new reactors. Two were abandoned during construction, and two entered service after multiple delays and major cost overruns (2023, 2024).

- New subsidies in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 were designed to keep existing units in operation and encourage new-generation Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). The Trump administration is expanding this Biden administration program with grants, guarantees, and executive orders.

- The quest for competitive commercial nuclear power has been long on promises and short on performance. Technological complexity and government policies have resulted in the worst of all worlds, with today’s situation not unlike that of the 1950s.

- A free-market approach to nuclear policy would entail the following: Ending governmental research and development in the field. Abolishing public grants and tax preferences for the industry. Halting foreign-loan guarantees. Repealing the Price-Anderson Act in order to privatize safety and insurance regulation. Lifting all antitrust constraints on industry collaboration. Making waste storage the responsibility of waste owners. Removing the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and the US Department of Energy from civilian nuclear policy.

Introduction

“With nuclear power, hardly anything is as it seems.”

– Marco Visscher, The Power of Nuclear (2024), p. 248

Commercial nuclear power has been praised as limitless, dependable, ultra-safe, emission-free, scalable, long-lived, and the fuel of the future. Once built, nuclear fission plants have relatively low operating costs compared to fossil-fuel generation. In today’s complicated energy mix, nuclear “is a reliable, high-capacity, high load mode of electricity generation, which makes it an ideal complement to various renewable conversion modes that still have mostly low-capacity, moderate-load, and unpredictably intermittent operations.”[1]

The operational physics of nuclear power represent, to many, “one of mankind’s greatest intellectual achievements … awesome, beautiful, elemental, and elegant; it gets down to the very roots of the universe.”[2]

Politically, federal support for nuclear under the Biden Administration has been significantly enlarged by the Trump Administration to date. Loan guarantees, direct investment, and executive orders are the order of the day.

But is nuclear competitive in a world of scarce resources versus competing ends? Splitting atoms to steam water to spin the turbines is a major undertaking, fraught with danger. Containing and controlling fission safely and reliably necessitates “the perfect machine,”[3] composed of complex, redundant infrastructure with long construction schedules. Financial economics is complicated by post-completion sales of price-undetermined electricity. Consequently, from the industry’s inception, special government favor and protection has been necessary for new reactors to compete against other forms of thermal generation.

Federal safety standards have resulted in costly overdesign. Regulators have been conservative and cautious, perhaps for ideological reasons. But given the liability limits of a nuclear accident imposed by the Price-Anderson Act of 1957, extended seven times to date, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), an independent agency, got to set the standards. This predicament invites consideration of free-market alternatives in place of federal rulebooks.

§§

In a free market, government would be neutral toward commercial nuclear power, as with other energies. Research and development would be private, grants and tax preferences absent. Insurance and safety would be determined under market conditions, not government incentives. Nuclear waste would also be privately managed without taxpayer support.

The institution of political capitalism (as opposed to free-market capitalism) has allowed government to become the dominant actor in this energy sector. Government-in-play allows special interests to gain control over the (less represented) majority of consumers and taxpayers. Concentrated benefits and diffused costs encourage government to favor those who lobby. Nuclear interests were there first.

What would a free-market nuclear industry look like in the US? For the 94 existing reactors (versus a peak of 112 in 1990), with capital costs sunk, operations would continue so long as marginal revenue exceeded marginal costs. With the average reactor being 40 years old and running well, most plants could continue running for decades.

The challenge is for new capacity given high up-front costs and long construction times. Simple economics favors new capacity powered by natural gas, oil, or coal in free-market settings. The future of the nuclear industry depends on government subsidies in the US (and elsewhere), and on the wherewithal of nationally planned economies, where most new reactors are being constructed abroad.

§§

There is significant support for new-generation atomic energy. Technological optimism abounds, with a call for less regulation for more competitiveness. Two recent books make this case.

In Nuclear Revolution: Powering the Next Generation (2024), Jack Spencer of the conservative Heritage Foundation calls for a “policy revolution” to unleash the potential of an energy source hitherto hampered by regulators and activists.[4] “The debate over the integrity of nuclear energy is over,” he declares. “Experience demonstrates that it produces good jobs, clean energy, and dependable power.”[5]

Robert Zubrin’s The Case for Nukes (2023), subtitled “How We Can Beat Global Warming and Create a Free, Open, and Magnificent Future,” is endorsed by notables such as Michael Shellenberger (Environmental Progress), Marian Tupy (Human Progress), and Alex Epstein (Center for Industrial Progress). “Nuclear power can provide the energy for an unlimited and magnificent human future,” Zubrin states. “But the technological revolution it offers has thus far been strangled by political constraints, mismanagement, poor decisions, and outright sabotage.”[6]

James Hansen, father of the climate alarm, endorses nuclear power as the only viable large-scale alternative to fossil fuels.[7] Microsoft-founder and Terrapower founder Bill Gates provides a “one-sentence case” for nuclear fission: “It’s the only carbon-free energy source that can reliably deliver power day and night, through every season, almost anywhere on earth, that has been proven to work on a large scale.”[8]

Political support springs eternal. “The case for nuclear power is a compelling one, not only for its environmental benefits, but also for economic, nonproliferation, and energy security perspectives that support our national and international goals,” Pietro “Pete” Domenici (US Senator, R-NM) wrote two decades ago.[9]

Most recently, a $900 million DOE loan program came with a call from Secretary of Energy Chris Wright of the Trump Administration:

America’s nuclear energy renaissance starts now. Abundant and affordable energy is key to our nation’s economic prosperity and security. This solicitation is a call to action for early movers seeking to put more energy on the grid through the deployment of advanced light-water small modular reactors.

§§

Left environmentalists have traditionally opposed nuclear reliance, beginning with safety concerns and continuing with economics. “What technology has the potential for wiping out cities and contaminating states after an accident, a natural calamity, or a successful sabotage?” asked Ralph Nader and John Abbotts in the 1970s.[10] “Nuclear power is in many ways this country’s ‘technological Vietnam’,” they added.[11] The forgone opportunity was “simple thrift” (conservation) or “the deployment of renewable energy supplies.”[12]

“Happy talk” about a “nuclear renaissance” defies experience, concluded M. V. Ramana, a professor of disarmament at the University of British Columbia. And it detracts from the mother problem, the limits to nature. “Pushing the nuclear agenda allows maintaining the false idea that the current pattern of development can continue indefinitely with no limits,” he concludes, “while climate change is solved by using one more technology from the same toolbox responsible for the problem in the first place.”[13]

Al Gore’s Marshall Plan to save the earth from global warming was dismissive of the largest emission-free resource. Perceiving “a great danger in seeing technology alone as the answer to the environmental crisis,” Gore demoted current nuclear designs as “a technological dead end.” Nuclear, consequently, was not “the key to solving global warming.”[14]

Wind and solar, with battery backup, can forestall new nuclear capacity more quickly and at less cost, many advocates contend. Energy engineer and Stanford professor Mark Z. Jacobson dismisses nuclear as pollutive in its (long) planning-to-operation phase, with resources better spent on “100 percent WWS [wind, water, and solar] across all energy sectors” to meet aggressive climate goals.[15]

§§

Countless books have described the business and political economy of commercial nuclear energy, many sharply for or against. There is general recognition that its problematic past was due to government over-inciting the technology, followed by a regulatory ratchet that created an over-engineered, overpriced nuclear fleet. This worst-of-all-worlds prompts the question of what would have resulted from a let the market decide approach during the last seventy years.

I. Historical Review

Industry Launch: Subsidies, Over-entry

During wartime, nuclear power was strictly a military operation of the U.S. government. Come peacetime, the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 created the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to control the technology, as well as the Congressional Joint Committee on Atomic Energy (Joint Committee) to oversee and fund it. Private development was not allowed, but between 1947 and 1954, $8 billion flowed toward prototypes with civilian electricity in mind.[16]

In its 1948 report to Congress, the AEC stated that though nuclear operational costs might be lower, “the cost of [constructing] a nuclear-fuel power plant will be substantially greater than that of a coal-burning plant of similar capacity.”[17] In the estimation of Arjun Makhijani and Scott Saleska:

There was no scientific or engineering foundation for the claims made in the 1940s and 1950s that nuclear power would be so cheap that it would lead the way to a world of unprecedented material abundance. On the contrary, official studies of the time were pessimistic about the economic viability of nuclear power, in stark contrast to many official public statements.[18]

§§

President Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace speech in 1953 signaled the high expectations and federal priority for commercial nuclear power, which were formalized in the Atomic Energy Act of 1954. In addition to “making the maximum contribution to the common defense and security,” this law demanded “the development, use, and control of atomic energy … to promote world peace, improve the general welfare, increase the standard of living, and strengthen free competition in private enterprises.”[19]

Privatization was one thing, commercialization another. But forces were gathering that would ensure government intervention would create the latter.

§§

Why push nuclear power beyond its military niche so quickly? Foremost, there was a heady confidence that a new era of energy abundance from US-led technology would result in a host of societal benefits. Scientists and engineers said so, and small experiments on the military side for ships and submarines proved the concept, cost aside.[20] The march of science would overcome obstacles, it was reasoned.

Unlocking the atom in peacetime was internationally prestigious for the country that started it all in wartime, and many Americans thought the peaceful use of atomic power might somewhat atone for its horrific wartime origin.[21]Plus, if not the US, who? Both allies, such as the United Kingdom, and adversaries, such as the Soviet Union, were racing ahead on the civilian front as well.

There was concern that fossil fuels, responsible for four-fifths of power generation at the time, were finite—with an end to come, even as soon as the 1970s.[22] On the demand side, electricity providers saw demand potentially doubling every decade. Utilities wanted this space and feared a federal or municipal takeover (“a TVA for nuclear energy”).[23]

Uranium was abundant and energy dense, which made it ideal for tackling the problems of the future, such as air pollution, a growing public concern that atomic energy could neutralize. (Passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970 to federalize the issue was just ahead.)

“Transmutation of the elements, — unlimited power, ability to investigate the working of living cells by tracer atoms, the secret of photosynthesis about to be uncovered … in 15 short years,” the chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, Lewis Strauss, exulted in 1954. “It is not too much to expect that our children will enjoy in their homes electrical energy too cheap to meter.”

In a 1962 report to President Kennedy, the AEC stated:

While the Commission has been proceeding on a considered course in general accord with its 10-year civilian power program adopted in 1958, that program is now on the threshold of attaining its primary objective of competitive nuclear power in high-fuel-cost areas by 1968.[24]

A continued, enlarged government push promised competitive nuclear power

as a means of exploiting a large, new energy resource; as an economic advantage, especially to areas where fossil fuel costs are high; as an important contributor to new industrial technology and to our technological world leadership; as a significant positive element in our foreign trade, and, potentially, as a contributor to the nation’s defenses. Its potential benefits will actually be realized, however, only if it can be made economically attractive.[25]

§§

Bullish talk from government and the nascent industry was not enough for utilities, municipalities, and the three federal power marketing agencies: the Tennessee Valley Authority (established 1933), the Bonneville Power Administration (established 1937), and the Southeastern Power Administration (established 1950). The cost and scale of a reactor was unknown, and safety and liability issues were paramount. Nuclear fission came with the fear of accidental radioactive contamination, a flash point with the public.

“By 1955, five utilities had announced plans to build nuclear electric plants, but none had acted,” noted conservative journalist William Tucker.[26] Democrats wanted government construction; Republicans looked to subsidies.

Both approaches — government construction and subsidies — were underway. In 1954, the AEC financed what became the 60-MW Shippingport project by Westinghouse Electric Corporation for Duquesne Light Company, which went critical in late 1957. Far from helping the cause, the cost overrun (50 percent) and high cost ($72.5 million, about $850 million in 2025 dollars) “left the utilities as uninterested in nuclear power during the late 1950s as they were a decade before.”[27]

Private financing for Shippingport fell short. By 1959, AEC expenditures of $586 million compared to $82 million from industry.[28]

§§

Liability protection for explosions or accidental discharges was under debate. Still, the “capital and operating costs of nuclear power were sure to be much higher than those of fossil-fuel plants, at least in the early stages of development, and the prospects of realizing short-term profits from atomic stations were dim.”[29] The Joint Committee told AEC to stoke private development or face federalization.

With the “industry [having] indicated little immediate interest in reactor development under the terms of the 1954 act,” the AEC created the Power Demonstration Reactor Program in early 1956 for special inducements. Government R&D was offered gratis or at fixed cost, and a seven-year waiver was available for enriched uranium, which the government solely owned.”[30]

Between 1955 and the end of the program in 1963, four major projects were developed. Industry consortiums (Power Reactor Development Company, Atomic Power Development Associates) chose a best way forward, although the AEC encouraged multiple designs, such as a highly problematic attempt by Detroit Edison for a fast-breeder reactor.[31]

Liability Limits: Price-Anderson Act of 1957

In 1956, Congress’s Joint Committee on Atomic Energy asked the AEC to assess the potential damage from a major nuclear accident. The following year, the Brookhaven Report, titled “Theoretical Possibilities and Consequences of Major Accidents in Large Nuclear Power Plants,” estimated that a 200 megawatt (MW) plant located thirty miles from a city could result in several thousand deaths, ten times more injuries, $7 billion in property damage, and 150,000 square miles of contamination. Companies and insurers were taken aback by this conclusion.

The nuclear radiation panic reached the public. Edward B. Lewis’s article in Science, “Leukemia and Ionizing Radiation” (1957), cautioned against background radiation, leaving the prospect of reactor releases disconcerting. Television appearances and other publicity for Lewis (a future Nobel Prize-winner in physiology) were a black eye for the “sponsor, participant, regulator, guardian and mediator,” the AEC.[32] This was despite reasonable scientific evidence that radiation fears were overblown, which later proved to be the case.[33]

§§

The elephant in the room for reactor development was the possibility of an accident. Nuclear technology was experimental. There was no data for insurance companies to set terms and conditions. Safety mishaps had occurred. “Everyone involved in the atomic-power program in the mid-1950s accepted the fact that atomic technology posed significant potential danger.”[34] A liability limit was necessary for reactor supply and demand to emerge.

Other generation options were cheaper. Coal was abundant, and natural gas was on the ascent with proven turbine technology and a maturing interstate gas transmission system. “Between 1963 and 1975,” reported one scientifically trained journalist:

gas turbine power plant capacity in the US increased by a factor of 70. Many of these turbines were essentially jet engines (aka “aeroderivative” turbines) redesigned to generate electric power.

The dash-to-gas, which nuclear orders also held back, was interrupted by federal wellhead price controls that put coal back into the driver’s seat by the late 1960s.

§§

Two years of intense negotiations began between government bodies and industry parties, including the US Chamber of Commerce, Association of Insurance Counsel, American Bar Association, and Federal Bar Association. Testimony before Congress established the fact that private insurance indemnification was far short of the destruction an accident could hypothetically produce.[35]

The head of Consolidated Edison Company of New York asked, “why not have the risk shared by all the people through the Federal Government,” since atomic energy was “in the interest of all of the people.”[36] Precedent existed with federal insurance for crops, floods, and banks, supportive parties argued.[37]

Rather than pause the process to let things sort out, with multiple designs shrinking to a few or even one (AEC’s “decentralization” approach invited many[38]), and let risk assessment improve with better information—a free market approach—the federal government would fill the gap. The infant industry was providing, in effect, a public good, said the political majority.

A charter member of Congress’s Joint Committee, and ultimately its chairman, Congressman Chet Holifield (D-CA), was critical of the commercialization rush. He noted the irony in 1955 hearings that:

…all these industrial groups which beat tom-toms and put articles in national magazines and built up a great propaganda drive that now is the time for private industry to come in and do a job, are suddenly becoming a little coy. They don’t want to plunge in, they are putting their big toe in the water and say it is a little cold, will the Government give us a little incentive?[39]

§§

The Nuclear Industries Indemnity Act of 1957 (Price-Anderson Act), “to protect the public and to encourage the development of the atomic energy industry,” authorized federal funding “for a portion of the damages suffered by the public from nuclear incidents, and may limit the liability of those persons liable for such losses.”[40] Licensees were required to obtain “available” private insurance, past which the federal government would be liable for as much as $500 million per accident. Firms were assigned an “indemnification fee” of $30 per megawatt per year for the government insurance.

With an antitrust exemption, insurance syndicates (three were formed) agreed to pay up to $60 million per accident, past which the Treasury would pay. The deal, vetted among the industry parties, was enough to remove a major barrier to nuclear commercialization.

With a liability cap estimated at one-fourteenth of the potential total cost of an accident, the taxpayer was put into play, and tort risk was otherwise placed on potential victims. “Nuclear exclusion” clauses in homeowner insurance policies from radiation damage were indicative of this.[41]

Critics wondered if the new law would lessen incentive for safety and cautionary siting.[42] Both industry and government were optimistic, however, that experience and the march of science would solve any problems.

Price-Anderson was scheduled to expire in ten years. No payouts occurred, but the private sector was not ready to stand on its own. The involved parties lobbied for $100 million per accident, which became $74 million in a 10-year extension in 1966 (about $750 million today), a small increase in real terms.[43]

§§

Behind the scenes, an updated AEC major-accident report, not released to the public, estimated worst-case deaths and damage at a multiple of that of a decade before.[44] This made the AEC part of the problem as promoter-regulator. Yet it was time to release “largely invisible, intangible, and undramatic” safety guidelines, and time was short.[45]

Construction Boom: 1963–1972

“The Price-Anderson Act opened the nuclear floodgates.”[46] With the insurance barrier removed, nuclear investment, while not the low-cost option, became attractive to utilities for another governmental reason.

Under state-level public-utility regulation, allowable profit was determined by a rate of return multiplied by capital investment based on original depreciated cost. The rate base would shrink (depreciate) over time. Utilities, while reimbursed dollar-for-dollar for “reasonable” costs, needed more rate base for steady or higher profit. Capital costs for a reactor were 50 percent higher than for a coal plant of the same capacity, if not more.[47]

State commissions could disallow “imprudent” costs of approved projects in rate hearings. Cost overruns were common in AEC projects. Hesitation by utilities remained despite the bullish presentations from General Electric, Westinghouse, and newer entrants that costs would diminish from learning-by-doing and scale economies to become competitive with oil, gas, or coal-fired generation.

§§

In 1961, the AEC reported that ten nuclear plants (mostly small) were complete and twice as many projects had permits to build.[48] But foreign developments seemed more robust, leaving nuclear as “a standby resource for the American economy, but one that could be perfected through experience gained abroad.”[49] A breakthrough was needed. General Electric, with only three orders through 1962, would provide that.[50]

In late 1963, Jersey Central Power and Light Company signed a fixed-priced turnkey contract with General Electric for a 515 MW reactor for “an astonishingly low price” of $66 million.[51] Construction began a year later, and the plant entered service in 1969 under a 40-year license from the AEC.

Jersey Central claimed parity with a fossil-fueled plant, which President Lyndon Johnson hailed as an “economic breakthrough.”[52] The head of the Oak Ridge National Laboratory announced a “Nuclear Energy Revolution” based on “the permanent and ubiquitous availability of cheap nuclear power.”[53]

Westinghouse matched GE’s terms for its own version of the light-water reactor.[54] Both companies, in fact, were taking the risk—and together would suffer losses as high as $1 billion, nearly half of the total plant cost, in their drive to capture the market and learn-by-doing.[55]

In 1966, cost-plus contracts replaced the unprofitable “de facto demonstration plants.” Still, the promotion “laid the psychological groundwork for … the ‘great bandwagon market’ of 1966–67.”[56] Seven reactor orders in 1965 were eclipsed by 21 in 1966 and 27 the next year.[57] Optimism ruled. The new industry was driven by subsidies and rate-base economics. Foreign orders came too, with federal financing through the Export-Import Bank.

Proven, improving new-generation technology, after all, would meet power demand growth of 7 percent per annum—and without smoke. The Northeast power blackout in 1965, affecting 30 million, the worst ever to date, created a safety issue of its own. Supportive state and federal authorities, as well as Big Science, blessed the utilities’ rush to lock in the future.

“Nuclear enthusiasts perceive[d] the technology as the obvious next step in an energy heritage that has already progressed through wood, coal, and oil/natural gas.”[58] AEC predicted a thousand reactors operating in the United States by year 2000. General Electric as late as 1974 expected a commercialized breeder reactor by 1982, the end of fossil fuels in power generation by 1990, and a virtual takeover by breeder reactors by the turn of the century.[59] But a report in 1969 by the highly respected Philip Sporn (retired president of a large utility, American Electric Power) estimated nuclear costs at double that of coal, which came in a year when new reactor orders began to drop off.[60] Existing utility heads would not speculate against what was seen as more upside, not downside.

Business Abroad: EXIM Financing

The government-enabled boom had another dimension. US nuclear developers were busy abroad, helped by the US Export-Import Bank (EXIM), a New Deal–financing agency. With its first commitment in 1959 (to Italy), EXIM’s nuclear portfolio would become its largest segment.

Domestic job creation was the traditional rationale for this agency, as well as the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC, founded in 1971). Other nations were similarly promoting their technologies, including nuclear power in the 1970s, such as Canada, France, and Germany. A third proffered reason came after the Arab Embargo in 1973: lowering global oil demand to reduce prices.[61] Countries inundated EXIM with requests to help finance nuclear plants to displace oil in power generation.

“None of the nuclear power plants sold [abroad] since 1967 would have been ordered without Exim loans,” the Government Accounting Office opined in 1973.[62] By first quarter 1976, EXIM’s cumulative commitments (loans and guarantees) neared 100 for $5.2 billion with an outstanding exposure of $4.2 billion. Recently inked deals in the Philippines, Yugoslavia, Taiwan, Spain, and Korea were expected to be joined by several billion dollars of commitments in the coming years.[63]

The lending boom ended quickly, mirroring the domestic market. “All told, there does not appear to be an example of EXIM providing financing in support of a US reactor to a new country since the 1970s.”[64]

§§

Domestic reactors were typically financed for 20 to 25 years with institutional investors, backed by the credit of the utility, itself protected by the regulatory compact of state commissions. Foreign projects were different. Bank loans of five years were not suited for commercial reactors, which could take up to seven years to build, with payouts often stretching another 10 to 15 years.

EXIM loans of 15 to 20 years could be double the term of the agency’s more usual 8-to-12-year loans.[65] A major subsidy of this program was postponing repayment until the reactor was operational, a grace period that could be as much as ten years.[66]

Retreat and Adjustment: 1973–Present

The nuclear boom was rudely reversed in the 1970s, with cancellations and completions revealing “almost certainly the costliest technical miscalculation of the twentieth century.”[67] Utility financing began to tighten in the late 1960s due to higher inflation (nearly 6 percent) and regulatory lag (the time between expenditure and reimbursement).[68] With the first cancellation in 1972, one hundred orders would be terminated in the next decade, representing nearly 100 gigawatts (GW) of planned capacity.[69] With the last order executed in 1978, nuclear capacity was destined to plateau.

Some reactors under construction were repurposed or cancelled. Consumers Power Company in Michigan (now CMS Energy) converted its 85 percent complete nuclear project to a gas-fired combined cycle plant after 17 years and $4.3 billion in outlays.[70] The William H. Zimmer Power Station in Ohio, facing costs of $3.1 billion, ten times its original estimate, was converted to coal in 1984. Originally announced in 1969 with completion expected in the mid-1970s, two 840 MW reactors had been reduced to one. Fines and lawsuits marred the project as well.[71]

Public Service Company of Indiana ran out of money with its half-completed $2.5 billion Marble Hill plant.[72] Commonwealth Edison lost its NRC license for its nearly completed $3.3 billion Illinois reactor.

The largest nuclear power project in history, formulated in 1968 for the Pacific Northwest by Washington Public Power Supply System, soured in the 1970s and 1980s when three units were abandoned during construction and another cancelled. Billions of dollars of fruitless expenditure led to the greatest municipal default in US history.[73]

Portland General Electric’s Trojan Nuclear Plant in Oregon, ordered in 1968 for $228 million, was completed two decades later at double the cost. Operational issues thereafter led to a lawsuit by PGE against builder Bechtel. But this was not a turnkey project with performance guarantees; it was a cost-plus contract. Bechtel prevailed; technical risk laid with the utility.[74]

High expectations for the breeder reactor to close the gap with fossil fuel generation, beginning with Detroit Edison’s Fermi 1, portended the future. “America’s fast breeder programme never got off the ground, and the continuing French and Russian efforts do not signal a mass breeder economy around the corner.”[75]

§§

Federal interest in nuclear power faded during the 1970s energy crisis. President Nixon appointed a new head of the AEC, James Schlesinger, who lectured the industry to solve its own problems and think about less demand, not more supply.[76]

President Ford was ambivalent, as costly completions came in. President Carter could only say, “as a last resort, we must continue to use increasing amounts of nuclear energy.”[77] And this was before the Three Mile Island accident in March 1979 that resulted in a de facto moratorium on new projects for decades.[78]

§§

The last nuclear plant entered service in 1990. Completions swelled the rate base that ratepayers had to cover. Consumer and environmental interests were now part of utility rate-case hearings, which resulted in cost disallowances, lawsuits, and reputational damage for utilities.

Fossil fuel plants, meanwhile, were benefiting from low energy costs and improving technology. With cheaper alternatives compared to the utility’s (nuclear-inflated) average cost, ratepayers wanted to buy their own power outside of the utility—if they could get it delivered. With the utility’s monopoly on transmission, legislative and regulatory reform became paramount.

End-users, beginning with industrials, lobbied federal and state lawmakers for mandatory open access, whereby transmission services would be offered at cost-based regulated rates for outside parties (independent generators and end users).

Open-access victories beginning in the mid-1990s would redefine the so-called regulatory compact.[79] Nuclear power’s cost inflation, in short, did much to upend the quiet, stable world of traditional public utility regulation in electricity.

II. Anatomy of Problems

“Non-turnkey plants ultimately cost about 175% of predicted costs.”[80] Nuclear plants that cost less than $1 million per MW in 1967 (2010 dollars) jumped to $3–$6 million by the mid-1970s.[81] Once completed, many plants underperformed.

“The failure of the US nuclear power program ranks as the largest managerial disaster in business history,” a Forbes editorial stated in 1985. Blame was placed on all parties: federal and state regulators, vendors, utilities, and contractors/subcontractors.[82]

In fact, nuclear power was never the great technology on the white horse. It was experimental and, with improvement, a backstop technology for electrical generation.

Safety was achieved. The cost and delay of nuclear plants, their overdesign, made the US industry arguably the safest of all energy technologies.[83] The mishap at Unit #2 at Three Mile Island in 1979—“history’s only major disaster with a toll of zero dead, zero injured, and zero diseased”[84]—compares favorably to the Deepwater Horizon offshore oil blowout (2010) that killed or injured two dozen.

§§

“It is hard to believe that a $200 billion industry with the potential to help solve the nation’s energy problems could be on the rocks—politically, technologically, and commercially,” a 1980s industry review noted. “Certainly the controversy surrounding nuclear power is unique; nowhere can we find a historical precedent for a technology that held so much promise but that is now virtually stalemated.”[85]

Such malinvestment had never happened before in the century-old US power business. Electricity was highly regulated, and nuclear the most government-subsidized sector within it. This was not coincidental, nor was it a market failure.

The “why” of nuclear’s underperformance was a combination of entrepreneurial error, technological complexity, and overregulation. The why behind the why was governmental. With insurance socialized, as well as cost and delivery taken on faith under public-utility regulation, the brakes were off.

Part of the problem with the nuclear dream was that hyperbole overtook reality as federal and state intervention encouraged reckless risk-taking with a new and complex technology. Interest rates rose significantly near the end of the boom, inflating the costs of capital-intensive, long-construction nuclear projects. Electricity demand growth fell by half in the troubled 1970s. Another part was regulatory overreach, magnifying the other issues.[86]

Complexity

Nuclear fission for electrical generation is inherently complicated “low risk, high-dread technology.”[87] “Safety must be built into every aspect of the design,” Terence Price explains.

A first safeguard is redundancy: a deliberate excess of protection systems. A second is diversity: a variety of different systems, operating in different ways, so that one systemic fault cannot put all of them out of service simultaneously. A third is rigorous use of the ‘fail-safe’ principle—so that if a failure occurs the system automatically places itself in a condition that is more secure, not less. A fourth precaution is the physical separation of vital functions—so that, for instance, a local fire cannot destroy the whole safety system.[88]

Utility fiefdoms (antitrust law prevented consortium strategies[89]) exacerbated the challenge of complexity. “As the US utilities opted for many individualized designs, rather than for a standard reactor, and as they began to build concurrently dozens of new plants,” Vaclav Smil concluded, “construction costs escalated, and they were pushed up further by changing requirements of new safety regulations.”[90] The expected learning curve and scale economies proved elusive.[91]

Learning-by-doing encountered numerous design and engineering problems, including “neglect of material embrittlement problems involving neutron bombardment, insufficient attention to cooling water chemistry and potential corrosion problems, a lack of appreciation of maintenance complexities and quality control problems, and a trivialization of waste disposal and decommissioning tasks.”[92]

A typical reactor had 40,000 valves, ten times that of a coal plant.[93] Repairs around a radioactive core differed from repair at other thermal (oil, gas, or coal) plants. A pipe failure at Consolidated Edison’s Indian Point Plant that took seven months to repair would have taken two weeks with far fewer, less specialized workers in a conventional facility.[94]

Utility management thought nuclear was “just another way to boil water and make steam.”[95] Not so. “A nuclear reactor requires 10 times the management intensity as a comparable coal-fired power plant,” one expert stated.[96] “[A] nuclear plant is a system—a system that requires an interdisciplinary perspective,” noted three MIT experts.

A failure in any one of the more mundane disciplines can be as disastrous as the failure of the most glamorous one. … Problems in the field are usually in areas that the engineers and scientists tend to take for granted.[97]

Rush

“No other mode of primary electricity generation was commercialized as rapidly as the first generation of fission reactors,” noted Vaclav Smil, with 25 years “between the first sustained chain reaction … and the flood of new plant orders after 1965.”[98] The cause behind that effect? “[N]o other mode of energy production has received such generous public subsidies,” with nuclear receiving 96 percent of all federal energy monies between 1948 and 1998.[99]

“We scaled-up nuclear reactors too fast,” admitted one federal regulator, “handed them out to the utilities too fast, and the technology wasn’t quite ready, and the utilities weren’t quite ready.”[100] Two economists wrote:

… the US nuclear power industry, the government included, in the late 1950s and early 1960s made a heroic decision to bypass the normal gradualism in the development and commercialization of a new technology—especially an exotic and extraordinarily sensitive technology like nuclear power—and to proceed rapidly to a $100 billion commitment, and ultimately far more. Numerous issues were too little understood, too little researched, and too little acknowledged.[101]

Environmentalism

“Being ‘anti-nuclear’ in the early 1960s meant opposition to nuclear weapons.”[102] Not-in-my-back-yard (NIMBY) activism was less ideological.[103] Some major environmental groups supported commercial nuclear, in fact.

This changed in the next decade, and definitively with Three Mile Island in 1979. Leading the opposition were the Union of Concerned Scientists, Friends of the Earth, and the Sierra Club (position reversal in 1975).[104]

“Opposition to nuclear power started rising in the mid-1960s,” summarized Michael Shellenberger.

From 1962 to 1966, only 12 percent of applications by electric utilities to build nuclear plants were challenged. By the beginning of the 1970s, 73 percent of applications to build nuclear plants would be challenged.[105]

The politicized environment expanded the forum for legal action and further regulation. “Between 1975 and 1983, 430 lawsuits were brought against the NRC, leading to 2,349 proposed rules and regulations—each of which required an industry response,” summarized Jack Spencer. “The additional and unexpected controls created industrywide uncertainty and raised questions about the long-term economics of nuclear power.”[106] Additionally, “state and local governments expanded their over-sight functions.”[107]

§§

Air quality standards emanating from the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1970 suggested a nuclear-for-coal substitution. But the upstart environmental movement became “closely bound” with “small is beautiful.” Soft energy (renewables, conservation) was in; hard energy (fossil-fuel and nuclear plants) was out.[108] Vaclav Smil described the triumph of emotion over reality.

A heady mixture of generation revolt, liberal activism, Schumacherian preaching, environmental concerns, nostalgic ruralism, back-of-the envelope calculations, and American faith in salvation through new gadgets produced a simplistic faith in passive solar heaters on every roof, clean electricity from photovoltaic cells … [and] in equally clean and captivating melodious power from the swooshing of assorted windblades, in benignly sweet-smelling fuel alcohols oozing from cozy farm stills fed with spoiled grain and fueled with dried straw or stover.[109]

The dilute, intermittent, and fragile nature of wind and solar made them ill-suited for the demands of the hard grid. Free-lunch conservation—or “a lunch you are paid to eat”—was magical thinking as well.[110] But this was the 1970s when Peak Oil and Peak Gas thinking predominated. Thus, in America, the “indigenous hassle-free alternative of cheap coal”[111] became the energy of policy choice under Jimmy Carter.

Today, environmental opposition to nuclear power is marked by concern for wind and solar displacement. Nuclear is too slow and costly in comparison, opponents contend, not unlike free market critics who favor fossil fuels for new capacity.

Informational Absence

Informational issues always plagued nuclear power. “The policy of secrecy not only inhibited commercial development of nuclear power in the United States,” wrote three MIT scholars, “but proved ineffective in preventing other countries from developing nuclear energy themselves….”[112]

The information problem went from government to industry. “[T]he nuclear industry’s absorption of the promotional attitudes of the AEC and reactor vendors was to plague its economic analysis for the next two decades.”[113] There was “selective publication of information.”[114] “Costs were underestimated and performance over promised in almost all categories, from plant construction duration to plant capacity performance.”[115]

“Technical reports underestimated future engineering problems, and available warnings about cost trends were ignored.”[116] Industry “self-deception” came from a lack of outside review.[117] “The fact that such crucial cost components have not been satisfactorily quantified,” Richard and Caroline Hellman wrote in their 1983 book on the subject, “reflects the primary difficulties in the nuclear power industry—inadequate available data and the technological and economic gap between design and performance.”[118]

Nuclear’s problems compromised the whole sector. Utilities “experienced a shock to their financial viability and a loss of public trust.”

The investor’s maxim that electric utilities “never lost money and never went broke” had run into a disturbing new reality. And the US nuclear industry, which had started the game with all the best cards, had lost its standing in the competitive global market.[119]

Overregulation

Government subsidies for commercial reactors set up the problem. Micro-regulation from Washington, DC, worsened it.

Early concerns were raised about potential overregulation of commercial nuclear.[120] How would industry leaders and regulators achieve best practice? Unfortunately, antitrust law precluded a united front, leaving some 15 interested utilities to collaborate with vendors to choose a favored technology.

AEC’s first safety hearing was in 1953. With the coming market, it was time to codify “standards, codes, criteria, and guides.”[121] AEC’s first radiation standards, going from protection of on-site workers to the general population, came in early 1957.[122] This would guide the Atomic Safety Board and Licensing Board, created within AEC in 1962.

The bandwagon effect featuring the Big 4 (Westinghouse, GE, Babcock & Wilcox, and Construction Engineer) overwhelmed the AEC.[123] “The constantly evolving designs produced unanticipated safety questions.”[124] What resulted “was excessively conservative and unpredictable,” noted Thomas Wellock. “The AEC believed there was no consistency in designs, the vendors believed there was no consistency in regulation.”[125]

Price-Anderson put regulators in charge, not companies and insurance providers. The outcome was ever-more-stringent edicts, a regulatory ratchet, which

was driven not by new scientific or technological information, but by public concern and the political pressure it generated. Changing regulations as new information becomes available is a normal process, but it would normally work both ways. The ratcheting effect, only making changes in one direction, was an abnormal aspect of regulatory practice unjustified from a scientific point of view. It was a strictly political phenomenon.[126]

Regulatory ratchet was “the way of the institutions of government.”

They begin dedicated to a greater purpose, and they end up serving themselves…. That was the way it was with the United States Atomic Energy Commission and its watchdog in Congress, the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy.[127]

In the swamp of Washington was

a fanatically defensive protectionist clique of tenured bureaucrats who have been drawing job security and prestige from the miraculous achievements of the Manhattan Project over twenty-five years ago, and whose best efforts since then have been divided between wildly inappropriate technological adventures and the justification of their past mistakes. [128]

Regulatory conservatism—err on the side of stringency—resulted in highly prescriptive, rule-oriented, legalistic control from Washington, DC. “The effects of this orientation,” summarized James M. Jasper, “include complex rules; opportunities for public participation; adversarial rather than cooperative relations between regulators and industries; a large role for lawyers rather than technical experts; inspectors expected to follow rules rather than use their discretion; and a large role for courts since regulatory agencies can be sued for improper administrative procedures.”[129]

§§

Nuclear safety was revisited in a 1988 book, Searching for Safety. Author Aaron Wildavsky took issue with the strict aversion rule that neglects the reality of irresolvable uncertainty, opportunity cost, and tradeoffs. Tolerable risk was the right response to the no-risk anti-technologists.[130]

When the opportunity cost of one risk is another risk, or just lost human betterment, then “risk taking can improve safety, and … ‘safety risks’ can be damaging.”[131] Nuclear power was a prime example. Too many safety devices, reviews, and procedures (“detailed prescriptive regulation”) can preclude electricity that otherwise would be generated by more risky or expensive methods.[132]

Recognizing safety as an entrepreneurial process of discovery, Wildavsky concluded:

Should we look upon safety as something we already know how to achieve, aiming directly at it by central command? Or should we view safety as something largely unknown, aiming at its achievement indirectly through a decentralized process of discovery?[133]

The economic viability of nuclear was not the subject of the above critique. But for existing nuclear operations, the issue was paramount.

§§

“Reforming the reactor licensing process has been an aspiration of five presidents,” Terence Price wrote in 1990. Having one license instead of two (because two had allowed “a measure of ‘design-as-you-go’” in the early years), as well as ending mandatory retrofits, could reduce construction time to “a reasonable six years.”[134] What had been five years before was now at least double that.

Stringent standards worked against safety. NRC rules became the maximum, not the minimum.[135] “Industry’s fixation on NRC regulations,” explained Joseph V. Rees, encouraged autonomous behavior in place of an industry-wide “standard of excellence.”[136] On-the-spot knowledge and judgment were regulated away.

§§

In 1985, nuclear project engineer John Crowley testified before Congress about an industry “once healthy and full of promise, now currently in disarray,” evidenced by “spiraling construction costs, prolonged schedules, a generally negative public perception, and an increasingly difficult regulatory environment.”[137]

Rather than grandfather design requirements at the start of construction, federal regulators issued new rules that required “reanalysis and redesign of numerous other systems and their supports,” what he called the “ripple effect.”[138]

Overall construction time doubled or tripled compared to what it had been before—what it was currently in France, thanks to “a nonadversarial regulatory climate” and “stabilization and standardization of their designs.”

“Federal regulations used to take up two volumes on our shelves,” Crowley related. “We now have 20 volumes to explain how to use the first two volumes.”[139]

§§

What about nuclear development abroad, often facilitated by US Export-Import Bank financing? France’s response to the Arab oil embargo provides a case study of nuclear done better. The country’s shift from fossil fuels to nuclear, resulting in 50 reactors by 1987, was not necessarily economical, however.

“No other country has matched her single-minded pursuit of an agreed national energy objective,” noted Terence Price.[140] It was not a free market but government central planning by Électricité de France SA (EDF). Standardization, while beneficial, was alleged by “detractors” to be “technocratic megalomania” at “enormous” cost.[141] “The debt incurred during France’s change-over to nuclear—232 billion francs at the end of 1989—is criticized by nuclear opponents for having ‘crowded out’ more profitable investment.”[142]

But overall, it was a technological success, economically endured, and without the opportunity cost of the US approach of design heterogeneity and micro-regulation.

III. Quest for Competitiveness

Retrofits kept the nuclear vendors going in the absence of new orders in the 1990s. What could resurrect industry growth in the US? The fast breeder reactor was not it, and nuclear fusion was stuck in the laboratory.[143] Simplification to reduce costs and construction time was much discussed but missing in action. Streamlined regulation was a perennial hope, but inertia prevailed. The only outlet for industry activity lay in improving operations.

§§

In 1991, President George H. W. Bush’s National Energy Strategy lamented “the hiatus in the reconstruction of new nuclear capacity.” The NES blamed an “impossibly cumbersome licensing process” and unresolved issues such as waste disposal for a “loss of public confidence.”[144]

The manifesto recommended general reforms (“remove undue regulatory and institutional barriers”). The report also cited the NRC’s work on “next-generation” light-water reactors, intended to result in substantial new entry by 2010.[145] This R&D would await Bush II’s Energy Policy Act of 2005 to result in new entry.

Fossil-fuel Competition

A rationale for civilian nuclear reactors was to supplement, and eventually replace, fossil-fueled power generation. Peak Oil and Peak Gas seemingly arrived in the 1970s—and again several decades later. But deregulation in the 1980s ended the oil and gas shortages, and technology improved with directional drilling and then hydraulic fracturing. (Coal abundance was never really in doubt.) The ultimate resource of human ingenuity under economic freedom overcame the limits of nature.

Nuclear commercialization undermined fossil-fuel generation from the beginning. “The coal industry’s ability to finance new mines or mining equipment is adversely affected by unfounded claims for nuclear power,” complained the National Coal Association in 1963, “and the financing of new conventional utility plants is also affected by the mistaken notion that nuclear power may obsolete them in a short time.”[146]

§§

A second loser was upstart natural gas. Simple turbines emerged from wartime jet propulsion technology. In 1949, the 3.5 MW Belle Isle gas plant, built by GE for Oklahoma Gas & Electric, ran successfully for decades. Total capacity of 240 MW a decade later was dwarfed by oil-fired turbines, not to mention the mainstays of coal-fired steam and hydro turbines.[147]

In 1965, a power blackout in the Northeast, impacting thirty million customers, revealed the need for natural gas peaking units that could quickly start in emergencies. Natural-gas-fired capacity of 1,300 MW would soar to 43,500 MW a decade later.[148] But disrupted gas supply from federal price controls in interstate markets would send demand to coal for the rest of the decade, delaying the implementation of new clean-burning, efficient cogeneration and combined cycle technologies.[149]

With 1980s price deregulation, the “dash for gas” was on. Gas turbines serving the peak were upgraded to provide mid-range and, like nuclear plants, baseload generation.[150] Oil, too, could substitute for gas in dual-fuel plants.

With nuclear reactor entry stagnant, natural gas technologies flourished until government-advantaged wind and solar power displaced thermal generation on the grid. The cogeneration/combined cycle boom, in retrospect, could have occurred decades earlier except for nuclear displacement.[151] Now, the best technology had another political foe.

“Nuclear Renaissance” I (Bush’s EPAct 2005)

In 2001, President George W. Bush’s energy report to Congress declared “the expansion of nuclear energy in the United States as a major component of our national energy policy.”[152] Expedited relicensing and other measures were proposed for existing capacity, but new subsidies to incite new construction went unmentioned.

This changed in Bush’s second term. Title VI of The Energy Policy Act of 2005 included federal subsidies for the construction of up to six new “advanced” reactors, as well as new funding for “Generation IV” research and development.[153] The Production Tax Credit (PTC), at 1.8 cents per kWh, in use with renewables, was offered for new entrants with “advanced” technology for the first eight years of operation.

With high costs and uncertain performance, Gen IV needed international support. The US Department of Energy formed the Generation IV International Forum, followed by a similar assemblage by the International Atomic Energy Agency the next year.[154]

In response to loan guarantees, cost-sharing, and PTC, 18 proposals were submitted for 29 new reactors, with the NRC issuing eight licenses for 14 projects.[155] A new 1,000 MW plant was estimated to cost between $1.5 and $2.0 billion, with construction expected to take five or six years, according to nuclear proponents at the time of EPAct 2005.[156] Four entrants, even with higher budgeted costs, would find out how over-optimistic this was.

Twin 1,100 MW reactors, Summer 2 and 3 in South Carolina, were abandoned during construction. Four years and $9 billion (almost the original cost of the project) was not enough to continue given $14 billion in estimated completion costs. Work stopped in 2017 when developer Westinghouse declared bankruptcy.

Two completed projects, Vogtle #3 and #4 in Georgia, were almost abandoned. The 2,200 MW project was budgeted at $14 billion over seven-to-eight years beginning in 2009. The project was completed in 2023/24 for $35 billion. But not before Westinghouse went bankrupt with its vaunted AP1000 Generation III+ pressurized water reactor technology in tow, leaving ratepayers on the hook despite relatively small cost disallowances against Georgia Power.[157]

“EPACT 2005 was supposed to keep the good times rolling for the nuclear industry by encouraging ongoing investment,” stated Jack Spencer. “Instead, it did the opposite.”[158] A lethal combination of subsidies and overregulation had claimed its latest victims.

Source: US Energy Information Administration

Entry was achieved after decades of stagnation (see above) but at great cost. Whether new reactors will enter service in the next decade(s) is a political question, not only a market one.

§§

The “renaissance” was capacity-negative: nuclear reactors, which peaked at 112 units in 1990, would decline to 94, reflecting industry stagnation and early retirements. The Vermont Yankee reactor was closed in 2014 due, in part, to protests from environmental pressure groups. Thirteen reactors entered decommissioning in the decade ending in 2022, most prematurely from subsidized competition from wind and solar power, a legacy of the Energy Policy Act of 1992 (Bush I). Around 10,000 MW of “reliable and clean power” was lost, most during the second term of the Obama years (2009–17) because of the rush to renewables.[159]

Retired nuclear capacity transferred some, if not much, generation back to fossil-fuel plants, an irony of Obama and DOE secretary Chu’s energy policy, which was “somewhat less about energy and more about a belief system.”[160]

§§

In June 2017, President Trump announced “six brand-new initiatives to … begin to revive and expand our nuclear energy sector … which produces lean, renewable and emissions-free energy.”[161] But with Summer-Vogtle problems manifest, little could be done. What was true back in the 1980s (“… nuclear power is an increasingly mature industry: there are few new technical surprises to report, simply steady consolidation and incremental development”[162]) had not changed.

“What is presented as simple, inexpensive, and close to market-ready always seems in reality to be complicated and expensive and never quite market-ready.”[163] A heralded “nuclear renaissance” from 2022 legislation is proving to be a familiar mirage.

“Nuclear Renaissance” II (Biden’s IRA 2022)

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, the high mark of the federal government’s “energy transition” push, was a life-saver for wind, solar, and other favored energies and technologies. Nuclear again demonstrated its bipartisan political support, with generous subsidies in search of another growth period.

The Act implemented an eight-year PTC of $0.015 per kWh from 2024 through 2032. For new “advanced” capacity, a $0.025 per kWh credit was granted for the first 10 years of operation, beginning in 2025. DOE’s Loan Programs Office was granted up to $40 billion in additional section 1703 loan authority, available through September 2026. Additionally, the IRA extends the Investment Tax Credit of 30 percent (and up to 40 percent) for facilities beginning construction before 2025 (not realized) and a “technology-neutral” credit for advanced nuclear for post-2025 entry.

The new hope was Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), another government play from start to finish. “[A] lot of the initial research and development is done on the taxpayer’s dime,” noted one critic.

The NuScale reactor design, for example, was the outcome of the Multi-Application Small Light Water Reactor project funded by the US Department of Energy and largely carried out in two public institutions: Idaho National Laboratory and Oregon State University. Likewise the virtual reality tools used by companies like Westinghouse … were funded by the DOE and carried out at another public university, The Pennsylvania State University.[164]

TerraPower, Transatomic, NuScale—SMRs are a taxpayer-funded, not market-driven, play, and are not commercially feasible. “By the late 1980s,” Vaclav Smil noted, “it had also become clear that the second option for the second nuclear era, the deployment of much better designed, smaller and less expensive but more reliable and inherently safe fission reactors, will not happen anytime soon.”[165] To date, none of the proposed projects has entered into construction, much less service.

“Nuclear Renaissance” III (Trump II)

The federal government continues to chase the nuclear dream. . Four executive orders by President Trump, in the words of the Energy Department, “lay out a plan to modernize nuclear regulation, streamline nuclear reactor testing, deploy nuclear reactors for national security, and reinvigorate the nuclear industrial base.”[166] International projects of domestic U.S. companies will receive financial and technical support from Trump agencies, one goal being “at least 20 new international Agreements for Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation by the close of the 120th Congress to enable the United States nuclear industry to access new markets in partner countries.”

The “bold new strategy for unleashing American energy and continuing our nation’s dominance as the world’s nuclear energy leader” is a refrain uniformed by history. “Currently, American policymakers are tripling down on this approach… to use taxpayer money to drive the advanced reactor industry forward,” warned Jack Spencer. “Hundreds of billions in taxpayer-backed loans are now available to fund nuclear projects, $2.5 billion is available to fund demonstration plants, and a plethora of tax subsidies have been authorized.”[167]

Nuclear subsidies are at play with recommissions, too. In Michigan, the 777 MW Palisades nuclear facility, closed in 2022, plans to restart in the next few years, enabled by a $1.52 billion DOE loan, as well as $300 million from the state of Michigan. The US Department of Agriculture has additionally allocated $1.3 billion to two rural electric cooperatives to buy Palisades power.[168] Most recently, a billion-dollar loan was approved as part of the Big Beautiful Bill’s Energy Dominance Financing program to restart a Three Mile Island reactor, part of an effort for fission to power new data centers. And a reorganization has created an Office of Fission within the Energy Department.

Favorable politics must meet and overcome the status quo of overregulation. “As of June 2024,” Spencer notes, “the NRC listed over eighty sources of regulation, including over two thousand pages of laws, treaties, statutes, authorizations, executive orders, and other documents[169][170]

IV. TMI: Failure and Reform

In the 1970s, average US reactor utilization was under 60 percent compared to the expected 70 percent, the result of “poor attention to quality,” including “inadequate testing of valves, lack of attention to the possibility of stress corrosion cracking, and flow-induced vibration, and underestimating the importance of water chemistry.”[171] Then came an event in 1979 that shook regulators and utilities to the core.

The accident at Three Mile Island inspired the formation of the Institute of Nuclear Power Operations (INPO), a “private regulatory bureaucracy created by the nuclear industry itself.”[172] Fifty-four utilities finally did what should have been done decades ago—collaborate. The worst reactor, after all, could put the other hundred in disrepute and turn the public and regulators against utilities. And the 900 MW Unit 2 in Middletown, Pennsylvania, with a 12-year cleanup ahead at a cost of nearly $1 billion, did just that.

Checking the regulatory boxes had brought out the worst in management. Nuclear was too complex and experimental for staid utilities and Washington, DC, regulators. INPO sought supra-regulatory standards of excellence[173] via shared knowledge from loaned employees under neutral management. It would work, with nuclear critics even suggesting that INPO replace the NRC.[174]

For its part, the NRC realized that its focus on hardware missed the institution using the technology.[175] Management processes and culture were key, which meant demoting regulation to liberate on-the-spot knowledge for spontaneous improvement. A wave of technical edicts prepared by the NRC after the Three Mile Island disaster was avoided.

INPO’s “communitarian” regulation was geared toward continuous operation.[176] Unplanned outages fell by half in the 1980s.[177] Average utilization, which had peaked in 1977–78, resumed in the late 1980s and improved thereafter. Capacity factors exceeded 70 percent in the early 1990s and 80 percent by decade-end. Capacity first reached 90 percent in 2002 and has remained above that level since.

The fruits of INPO were at work, but so was enhanced incentive. With more reactors becoming price-unregulated “merchant” plants, profit-maximizing owners did the right things. This worked until premature reactor retirements occurred from lower margins from government-subsidized wind and solar facilities.

The World Nuclear Association reported “remarkable gains in [US] power plant utilisation through improved refuelling, maintenance and safety systems at existing plants.”

Average nuclear generation costs have come down from $51.22/MWh in 2012 to $30.92/MWh in 2022. This 40% reduction in nuclear generating costs since 2012 has been driven by: a 41% decrease in fuel costs; a 51% decrease in capital expenditures; and a 33% decrease in operating costs.

Better efficiency allowed nuclear to retain its 20 percent market share of growing US generation. “It is as though the nuclear fleet were doubled without actually building any new plants.”[178]

Expert Error

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex,” President Eisenhower warned six years after his Atoms for Peace speech. “The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.”

Little did Ike realize that his civilian nuclear ambitions would spawn its own complex of power, with government enabling a new industry when the free market’s invisible voice was saying not yet, go slow, wait-and-see.[179]

Enter expert failure, defined as “any deviation from a normative expectation associated with the expert’s advice,” within the entangled deep state.[180]

Those paid to share their knowledge failed repeatedly. What dosage of radiation from a nuclear reactor was safe? Competing theories resulted in the wrong verdict (the linear no-threshold model).

What was the cost of a new reactor? Wrong again, from the turnkey contracts by GE and Westinghouse in the 1960s to the projects pursuant to the EPAct 2005.

What amended regulation was necessary to ensure safety? Much overwrought regulation came from the Atomic Energy Commission and its successor, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, in their issuances (Opinions, Decisions, Directives, Guidelines, Petitions, Rulemakings).

§§

“When experts disagree, whom shall we believe,” asked the editors of a 1982 book on the pros and cons of nuclear power.[181] Exploring expert failure several decades later, Roger Koppl differentiates between knowledge imposed on the system from above versus the bottom-up, fragmented, even inarticulate knowledge that flows as price signals and profit/loss.[182]

Expert error flourishes where “the object domain is complex, uncertain, indeterminate, or ambiguous,” Koppl explains, where “feedback mechanisms may be weak or altogether absent.”[183] This certainly applies to the nuclear commercialization, where natural outcomes were overridden by lawmakers pushed by self-interested businesses. Scientists joined in, enthralled by a new domain and in pursuit of “identity, sympathy, approbation, and praiseworthiness.”[184]

In the wonderland of electricity, the Big Players coalesced. But major government intervention at the federal and state level was required to let expert error win. Koppl’s closing advice, “value expertise, but fear expert power.”[185]

Public Policy Reform

“I would repeal the Price-Anderson Act and use the threat of accident liability to discipline private sector nuclear activities,” wrote one progressive left author nearly 30 years ago. “I would require the utilities and nuclear investors bear the full costs of any future nuclear power project and cost overrun risks.”[186] Such is also the free market, classical liberal view versus the bipartisan view of government reform-and-subsidy, reflecting technological optimism for some and a distrust of fossil-fuel generation to others.

The spirit for fundamental change toward a free market lurks, however. “Policymakers should create an entirely new framework for commercial nuclear energy,” states nuclear advocate Jack Spencer, “that is wholly rooted in free enterprise, innovation, and competition.”[187]

What specific reforms are called for? First, the nuclear power industry should be removed from government support, domestically and internationally (via EXIM). Three reactors owned by the US government’s Tennessee Valley Authority should be sold and privately managed. Government policy at all levels should be neutral toward all energies and related technologies, including nuclear power.

The nuclear promotional activities within the US Department of Energy should be terminated, while the Nuclear Regulatory Commission should eliminate its civilian-side programs, leaving military-related activities for transfer to the US Department of Defense.

§§

Defunding civilian nuclear to end subsidy programs would entail abandoning the sacrosanct Price-Anderson Act of 1957 cap on nuclear liability exposure, extended seven times to date. Far from disrupting the industry, terminating Price-Anderson could be a win-win. Collected monies in the nuclear fund ($8 billion) would help fund the transition to entirely private insurance. Each owner of a reactor would obtain insurance and, short of that, carry a potential liability against the capital of the firm.

Investors and other financial stakeholders would judge reliance and safety, not Washington, DC. Radiation (such as the controversial linear no-threshold limit) and other standards would be determined by the parties informed by science. What would a judge or jury believe in this regard?

The quasi-governmental Institute of Nuclear Power Operations, discussed above, would be central in a post-NRC environment. The experience and reputation of INPO makes this changeover doable and appealing.

§§

“To achieve free-market conditions for nuclear energy,” in Spencer’s estimation,

the federal government must create a predictable and reasonable regulatory environment, enact a market-based waste-disposition program, and stop subsidizing specific technologies and firms. Perhaps most importantly, Washington needs to stop subsidizing nuclear energy’s competitors.[188]

The premature retirement of nuclear capacity from wind and solar subsidies, namely the Production Tax Credit and the Investment Tax Credit, would cease. Nuclear itself would no longer receive the same subsidies as currently embodied in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

“[N]o one truly knows how economical (or not) nuclear power could be if it were allowed to exist in a free market,” Spencer allows. Would the entry of new reactors be stymied? That verdict awaits free market conditions without subsidies on the one hand and overregulation on the other.

V. Conclusion

The perennial quest for a national energy policy—a centralized governmental approach subsidizing some energies and/or penalizing others—has prominently included nuclear commercialization. Nuclear power received almost all federal energy-related research and development monies in the second half of the twentieth century.[189] Today, under Trump II, nuclear subsidies have again risen to the top.

Has this major government foray been successful? Air-quality benefits have resulted from nuclear-for-coal and nuclear-for-oil displacement in power generation. But nuclear’s resource commitment, including decommissioning costs to come, has been enormous, even unprecedented. This economic premium is what could have gone to other, higher uses in a world of scarce resources versus unlimited wants. One opportunity cost has been technology improvement and retrofits at coal plants to reduce emissions of criteria pollutants.

The past is a sunk cost. Currently operating nuclear plants can be presumed to be economical. They deserve little political opposition or ideological spite. Their continuance should be judged in terms of incremental revenue versus incremental cost (including decommissioning costs) with neutral tax treatment between power generation energies and technologies.

Regarding new capacity, light water reactors still have not demonstrated their economic viability versus other forms of thermal generation. The Small Modular Reactor (SMR), currently in vogue, is a government-enabled backstop technology for (cost-effective) electrical generation. In nationally planned economies, on the other hand, nuclear projects are being chosen and completed for reasons of their own.

The three dimensions of commercial nuclear are science, technology, and economics. “Do not overemphasize science and underemphasize engineering,” three energy technologists warned.[190] To this it can be added: Do not overemphasize engineering and underemphasize economics. Of the technological possibilities, only a small subset is economic, defined as creating more value than cost as judged in a free market. In this sense, Vaclav Smil has called nuclear power a successful failure, “a partial (if very expensive) success.”[191]

§§

Political Economy 101 explains government promotion, indeed enablement, of nonmilitary nuclear power since the 1950s. The knowledge problem of government intervention resulted in layers of expert failure. Unintended consequences from government intervention emerged from complexity. Expanding government intervention to address the problems created by prior interference magnified problems and prevented fundamental reform.

Concentrated benefits and diffused costs drove a nonmarket “market.” Regulatory capture was in play on each side at different times, from the regulated industry to the anti-nuclear movement. The mixed economy of political capitalism provided the framework, not government ownership and control as some lawmakers wanted at the beginning.

What critics call the Nuclear Industrial Complex continues with bipartisan political support. Environmentalists critical of industrialization and growth now find opposition from other “green” groups favoring nuclear power as a much larger, scalable source of emission-free electricity. A true free market solution is not yet part of the conversation.

§§

“The first step in resolving the nuclear controversy,” noted a study more than 40 years ago, “is to bridge the gap between what the experts know and what the public needs to know.”This should have happened at the beginning, the authors added, to have avoided much of the problem.[192]

This problem continues with optimistic public pronouncements by industry and government not joined by actionable contracts and execution. The inherent complexity of nuclear fission compared to other forms of thermal generation suggests a problem that is not soon to go away.

Fundamental free market reform is the best way forward. As mentioned in the previous section on policy reform, current government subsidies should cease, and regulatory oversight privatized to the (existing) Institute of Nuclear Power Operations. Government-owned nuclear plants under the Tennessee Valley Authority should be sold, and foreign programs under the EXIM bank terminated.

The existing nuclear fleet (94 reactors) would be subject to a financial test in a true free market. Affordable capacity would cover private insurance costs in place of existing Price-Anderson protection. Collected monies under federal law for waste storage and future decommissioning would be returned to the companies with their obligations unchanged.

Margins would improve with the end of de facto predatory pricing by tax-advantaged wind and solar, preventing premature nuclear retirements (as in the past). The tax credit for production, however, would cease.

New nuclear capacity would also be determined by market forces. Current tax preferences for new investment would end, as would government-funded research and development. Insurance subsidies, too, would terminate on the government side, leaving private arrangements for presumed-to-be safe nuclear operations.

§§

“Not the soberly calculating businessman but the romantic technocrat is to blame for a delusive incomprehension of reality,”[193] observed economist Ludwig von Mises before the advent of nuclear power. With the peaceful atom, romantic, magical thinking took over with government intervention, ensuring its rushed introduction and growth—and stagnation and underperformance thereafter.