In the late nineteenth century, local governments in Britain invested substantial sums in running water infrastructure. Running water made cities more attractive and also reduced the prevalence of waterborne diseases. The tradeoff was a massive increase in human-waste pollution being thrown into Britain’s rivers and estuaries.

Shellfish, which were immensely popular among British workers, fed in these polluted waters. Absorbing bacteria from human sewage, they acted as a key source of typhoid contamination (via salmonella). Initially, the connection between sewage water, shellfish and typhoid was unknown. As a result, the initial reduction in typhoid fever (and other water-borne disease related deaths) petered out and plateaued. This was because, as more and more lived in cities, more and more people consumed shellfish that were increasingly being collected from polluted sites.

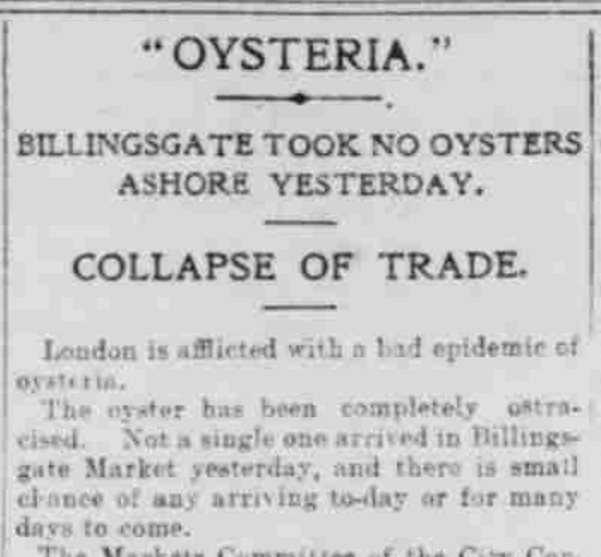

However, the connection gradually became apparent. As consumers connected the dots between oysters and typhoid, panic set in. Headlines in major newspapers warned of “polluted shellfish” and “oysteria.” The entire seafood industry faced collapse. In the first few months of 1903, after a well-publicized case of infection at a Christmas party, consumption reportedly collapsed by as much as as half. The industry faced collapse because consumers were unable to sort “bad” shellfish from “good” shellfish.

Governments did nothing, in part because they did not understand the problem very well, and in part because things evolved too fast for them to act. Private actors resolved the problem within less than a year. The industry self-regulated, typhoid mortality fell like a rock from the sky, and the shellfish industry recovered from a shock that could have been fatal.

The Worshipful Company of Fishmongers was a largely honorary association of fish merchants who were tasked with running quality control at London’s (city-owned) Billingsgate market. In other words, it was a form of private-public partnership (PPP). Many large firms and oyster merchants were part of the Company. They sold through Billingsgate. If the shellfish market collapsed, they lost their distribution channel, their customers, and their income. They had every reason to prevent that. Rapidly, they used their inspection powers to ban shellfish from known polluted sites. They hired a bacteriologist who went around the country to test water at known harvest sites. Within a year, he conducted hundreds of costly tests. Fearful of lawsuits, they began suing deceitful or careless fish merchants who came to Billingsgate.

Although it was in a PPP at Billingsgate (the central market in London, which was Britain’s main fish market), the Company could not prevent fish from being sold elsewhere—on the docks, in rival markets, or through private transactions. To maintain dominance, it had to offer higher-quality, safer products. The name of “Billingsgate” became a brand premium of sorts. It allowed consumers to distinguish “good” shellfish (which sold at a premium at Billingsgate) from “bad” shellfish (which was cheaper because of the uncertainty). This segmentation allowed the market to bounce back but also consumers to find the most effective solution. Other city markets – such as those in Manchester – simply ended up copying the approach at Billingsgate to avoid the tag of “bad” shellfish.

Although the crisis was clearly over by 1906, the government was still discussing solutions that private actors had already dismissed as ineffective or impossible to implement. A year before the Great War, governments were still discussing solutions.

We underestimate the ability of markets, civil society and property rights to act in ways to resolve complex environmental problems. We also overestimate the ability of governments to provide effective solutions to complex environmental problems. That was the clear finding of this historical illustration (which is the result of joint work with Nicky Tynan of Dickinson College) of shellfish and waste water in Victorian London.

All the elements illustrate my point that we underestimate the potency of markets and overestimate the abilities of governments. Environmental problems always emerge when no one clearly owns (or is responsible for) a shared resource (air, water, fisheries). The result is that people overuse, pollute, and spoil the resource. Here, the water was the shared resource.

To remedy the pollution, one can choose to impose restrictions to access the shared resource (tax emissions, ban harmful practices, prohibit access). Or, one can engage in what jurist John Hasnas calls “common-law privatization” — letting decentralized actors regulate through mechanisms like property rights, tort litigation, and consumer-led reputational pressures.

The latter solution rarely gets good press. “Something has to be done, now” and “the problem is too big” are the most common refrains. To be sure, if there is an emergency, the government-restrictions approach may have the upper hand. The same might be true if the complexity of the problem — for example, climate change or water pollution — is too great for private players to coordinate effectively. But it also has downsides. Governments tend to apply one-size-fits-all solutions because they both lack information about local peculiarities and the ability to be flexible. They are also exposed to the possibility of interest groups trying to shape the rules in ways that benefit them. Finally, by their size and lack of a profit motive, it is hard for them to interpret new information in ways that allow effective solutions to emerge.

In contrast, the “common-law privatization” allows multiple solutions to be tried simultaneously in multiple contexts. This allows for more flexibility in adjustments. By being exposed to tort-related lawsuits, people are incentivized to act preemptively to avoid lawsuits, protect reputation and retain market access. Harm prevention is thus privileged. Because solutions emerge by private ordering, there is little to no room for politics. Thus, cheap and effective solutions can emerge.

In London’s shellfish market example, governments should have had the upper hand. Yet, private actors outpaced the state in protecting public health and the shellfish industry. In months, very elaborate solutions were deployed and were based on building trust. Rapid solutions needed to be deployed. Otherwise the industry would have collapsed entirely. Not only were the private solutions rapidly deployed, perfected, redeployed and re-perfected again. Governments were insanely slow in providing any coherent response (if they responded at all).

The scale of the problem was also pretty large. The shellfish industry was not a minor industry nor was it a minor staple (the East End of London was known for cockles, mussels, and whitebait – all of which were subject to the contamination problem). There was a clash with another imperative – the provision of safe drinking water – which meant that multiple issues were connected. This made the problem somewhat complex. Yet, the private solution was rapidly deployed and was superior.

In fact, the problem even emerged because of clashes between governments. Sewer upgrades before the 1890s to protect drinking water often diverted waste to estuaries, contaminating shellfish beds. They fueled the problem! When the time for solutions came, local governments and the national government were clashing over these diverted waters for many years while the private players simply found a workaround solution within less than a year.

Don’t get me wrong—there are environmental problems where governments may genuinely have the upper hand. But the case of shellfish and typhoid in Britain suggests we might be overestimating how often that’s true. Maybe, just maybe, we need to reframe the discussion. Before reaching for government restrictions, we should first ask: is there anything we can do to let private solutions emerge more quickly? Are there ways in which government action is making the problem worse? Elsewhere, I pointed out that there exist large subsidies to multiple industries that emit greenhouse gases. By propping up these sectors with subsidies, one magnifies the climate change problem. Likewise, governments across the world subsidize fossil fuel consumption indirectly and thus discourage energy efficiency investments. Are there things the state is doing that block private-order solutions from forming? Only once we’ve answered those questions should we ask whether government restrictions are truly the last resort.