How do property taxes work in the United States, and what are their economic consequences? This AIER Explainer explores how property taxes are enforced, how much revenue they generate, the debate among economists about whether property taxes are “good” taxes, and steps lawmakers can take to keep property tax burdens reasonable.

What Property Taxes Are

Property taxes are taxes on the assessed value of property. Currently, only the value of real estate is taxed, not personal property, unless you have a business. Historically, state and local governments often did tax the personal property of households, which made the property tax essentially a wealth tax. Massachusetts’ “faculty tax,” which in colonial days assessed and taxed a person’s income-earning potential, technically survived until the early twentieth century. States gradually moved away from taxing real estate value in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as alternative revenue sources like income and sales taxes became available. Most modern property taxes are levied by local governments (counties, municipalities, sub-municipal bodies like villages and townships, and special districts).

Today’s property tax systems still involve assessment of real estate value by a local official. Assessors attempt to use comparable properties nearby to estimate the value of the land you own and the structures on that land. Every property owner in a jurisdiction faces the same tax rate, so the higher the assessed value, the more tax is levied.

States try to standardize assessment practices across localities, and most states have some sort of process to “equalize” local assessments to statewide market prices. These equalization procedures became important from the 1960s onward, as state legislation and court decisions drove efforts to redistribute money from “property-rich” to “property-poor” localities for the purpose of school finance.

Property taxes are often paid into an escrow account as part of a monthly mortgage payment. The mortgage lender then pays the taxes from the escrow account when they are due. For real estate owned without a mortgage, or when the lender does not require escrow payments, property taxes are typically paid directly to the local government once or twice a year.

Statistics on Property Taxes

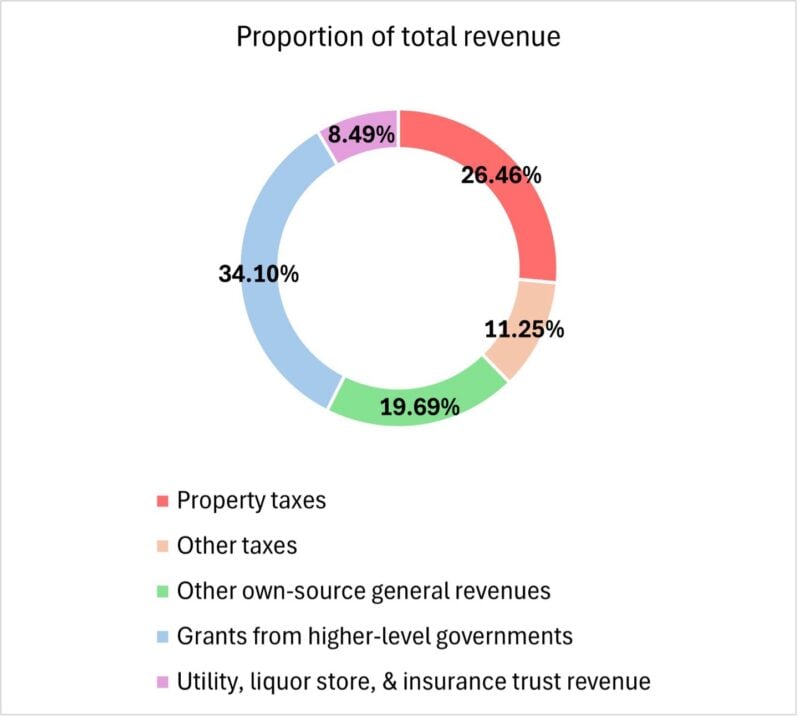

The US Census collects data on state and local finances. In the US, state and local governments raised about $650 billion in property tax revenue in fiscal years ending in 2022, amounting to 27 percent of all state and local tax revenue. Ninety-seven percent of property tax revenue is local rather than state. Local governments rely on property taxes for over a quarter of their total revenue and about 40 percent of “own-source” revenue—revenues raised by local governments rather than given to them by higher-level governments (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Local Revenue by Source, U.S., FY 2022

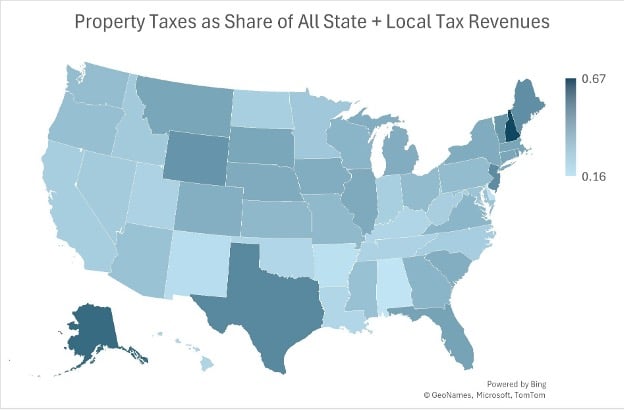

Individual states’ dependence on property taxes varies with how fiscally decentralized they are. That makes sense, since property taxes are a quintessentially local form of revenue in the US today.[1] The most property-tax-dependent state, by far, is New Hampshire, where over 61 percent of all state and local tax revenue comes from property taxes. Number two is Texas, where 41 percent of state and local tax revenue comes from property taxes.

The least property tax-dependent states are Alabama and New Mexico, both of which get under 15 percent of their tax revenue from property taxes. Both states have essentially centralized school finance under state government, so property taxes largely go to noneducational functions of local government, such as roads, police, fire protection, and parks. Alabama relies heavily on sales and individual income taxes for revenue, while New Mexico depends most on taxes on gross receipts, individual income, and mineral and hydrocarbon severance.

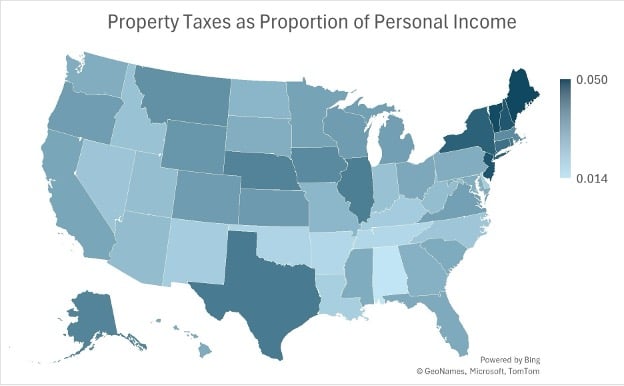

Fig. 2 displays a heatmap of property tax dependence for all 50 states. Fig. 3 maps property taxes as a share of personal income for all 50 states, a reasonable proxy for property tax burden (though it overstates the burden of property taxes on residents in states with a large share of seasonal homes).

Fig. 2 Property Tax Dependence in the States

Fig. 3 Property Tax Collections Divided by Income, by State

The Economics of Property Taxes

Economics can help us answer two questions about taxes: How much do they discourage productive economic activity? And on whom does the “incidence” of a tax fall — in other words, who really pays it? The answer to the latter question can also help us understand whether a given tax is “progressive” or “regressive,” that is, whether more affluent households pay more or less of the tax.

When it comes to determining the economic impact of property taxes, economists consider two possibilities.[2]

The first possibility is that the property tax is a “capital tax.” This assumes that real estate wealth is a form of capital, and higher property taxes reduce the return to capital. If the property tax is a capital tax, it is a relatively wasteful but progressive form of taxation. Taxing capital is wasteful because it discourages investments that increase the productivity of human labor. It’s a bit like eating your seed corn. Taxing capital may nevertheless be progressive if it primarily reduces the incomes of the people who get their incomes from investments, who tend to be wealthier than average. Taxing capital may not be progressive, however, if it strongly discourages investment, because then workers will be less productive and earn lower wages.

The second possibility is that the property tax is a “benefit tax,” that is, a tax that works like a user fee: the more you benefit from public services, the more you pay in tax. If the property tax is a benefit tax, it doesn’t discourage investment and isn’t wasteful. It would approximate a competitive market price for the services you get from your local government.

It’s important to note that economists — unlike many politicians and activists — generally don’t view property taxes as regressive. While lower-income households may pay a larger share of their income in property taxes, that’s only part of the picture. Economists consider equilibrium effects: higher property taxes can lead to lower rents and home prices or greater benefits from public services, offsetting the initial burden.

To understand the economics of property taxation, start with the understanding that people are mobile, but land is not. This fact has led many economists to be fascinated with the land-value tax, that is, a tax on the unimproved value of land, excluding structures. Henry George even believed that a single tax on land should replace all other taxes.[3] Milton Friedman called the land-value tax “the least bad tax.”

The reason economists have sometimes been fascinated with the land-value tax is that the immobility of land means that taxing its value causes no distortions. There’s nothing the landowner can do to escape the burden of a land-value tax, because its value is set in the market and determined by the general demand for land in the locality.

In practice, however, land-value taxation has been infeasible because it is difficult to assess what the value of a piece of developed land would have been had it not been developed. It’s especially difficult to do this assessment when there aren’t many comparable pieces of undeveloped land, as in built-up cities.[4]

Assessing the value of real estate, including improvements, is much easier, because it is easier to find comparable properties. But taxing the value of improvements can also discourage property owners from upgrading or developing their land.

On the capital-taxation view of the property tax, real estate is partially interchangeable with other forms of capital investment. Therefore, the higher the property taxes, the lower the return to capital in the economy in general (because people will pull investment from real estate and put it into, say, the stock market, reducing the return to capital).[5] Since owners of capital tend to be richer, this theory says that the property tax is progressive.

In the view of public economist and property tax researcher Peter Mieszkowski, property taxes also have a consumption-tax aspect. His model predicts that workers and landowners in places with higher-than-average property taxes suffer an “excise tax” that is roughly equivalent to a subsidy for workers and landowners in places with lower-than-average property taxes, so the net effect of average property taxes on the national economy is to reduce the return on capital. To the extent that property taxes therefore discourage business investment, then just like corporate income taxes, they might not be very progressive after all, because lower business investment reduces labor productivity and wages.[6]

The benefit-tax view comes from Charles Tiebout’s model of household choice of local government.[7] If there are lots of local jurisdictions, it’s easy for households to move from one to another. If, further, the costs and benefits of taxes and public services tend to stay within the borders of each jurisdiction, then people will tend to “sort” into communities that offer the mix of taxes and public services that best suits their preferences. In fact, Tiebout’s model is one of only a few ways economists have discovered to provide “nonexcludable” goods efficiently. (Nonexcludable goods can’t be withheld even from people who don’t pay for them, giving people an incentive to “free-ride” and accept the benefits without contributing. An example is a national missile defense system — you can’t let people opt out of paying for it because they’ll still be protected regardless of whether or not they pay.)

Now, suppose that households pay for local public services with property taxes. If a local government taxes too much and offers poor-quality public services, then families and businesses won’t want to move to that jurisdiction. As demand for real estate falls, so will property values.

Because your property values fall by the amount of the waste, you as a homeowner can’t really “escape” if your local government becomes wasteful. Some economists see this as a negative of property taxes.[8] But it’s also a positive, because it means property taxes don’t distort behavior as much. A local income tax, by contrast, would drive workers to flee to lower-tax jurisdictions even if wages were a bit lower there, meaning that labor wouldn’t necessarily be allocated to where it’s most productive.

Because homeowners’ (and businesses’) property values fall if their local governments provide bad value for money, homeowners and businesses have a strong reason to monitor their local government for good performance, claims economist William Fischel.[9] Indeed, homeowners are far more likely than renters to vote in local elections and participate in public hearings.[10] Economists disagree about how effective “homevoters” are in making local governments efficient.

On the “benefit tax” view, property taxes are good because households sort themselves into jurisdictions that offer higher or lower levels of taxes and benefits. Property taxes are then simply the market price for local public goods. More precisely, the services that local governments provide (parks, schools, security) become “club goods,” excludable to nonresidents who don’t pay property taxes, rather than “public goods,” which are nonexcludable.

For this result to be obtained, households have to sort themselves not just by tastes but by ability to pay. Otherwise, lower-capacity households would “chase” the wealthy, to enjoy high-quality public services at low cost. Some economists have suggested that localities can use zoning regulations to prevent “free-riding” by effectively requiring households to purchase enough property that the taxes they pay will cover the cost of the services they enjoy.[11]

The cost of this policy solution is greater socioeconomic segregation. Localities might still want to allow some socioeconomic diversity because different types of labor are complementary – thus, property values might be higher and taxes lower if local businesses have access to some less-skilled labor – but decentralization of local finance and zoning does lead to a considerable degree of socioeconomic segregation in the real world.[12]

With zoning regulations restricting housing supply in many parts of the US and driving up costs, some states are now moving to preempt or override local rules to expand housing access. If state preemption fully eliminated fiscal zoning, then we would expect property taxes to operate more like a capital tax, because lower-income households would be attracted to wealthier jurisdictions where they could free-ride on the taxes paid by wealthier households.

But property taxes also give local jurisdictions a reason not to make their zoning regulations too strict. Allowing multifamily and commercial development, in particular, grows the property tax base and reduces the burden on existing property owners.[13] In fact, the states with the strictest limits on development, like California and Hawaii, are also among the least property-tax-dependent states, while Texas, the most open state to development, has high property taxes.

Economists agree that property taxes are, in fact, some combination of a benefit tax and a capital tax. Where they disagree is the extent to which one view or the other better describes the majority of property tax systems. The benefit-tax view helps us realize that to understand how the property tax works, we also need to understand what it pays for. The capital-tax view helps us realize that the more the situation deviates from the ideal model of competitive, self-funding local governments, the more progressive and inefficient the property tax is.

It has been difficult to design empirical studies to test the benefit-tax and capital-tax views. One study, however, firmly shows that, as expected, a property-tax increase with no local benefit works like a capital tax.[14] This study investigated a school finance reform in New Hampshire, in place from 1999 to 2011, that redistributed property tax revenue from high-property-value municipalities to low-property-value municipalities. As the capital-tax view would predict, property values fell in the places that lost revenue (and had to make up for it with tax increases and spending cuts) and rose in the places that gained it (and could then cut taxes). Moreover, in places without strict zoning regulations, property values didn’t rise as much, and instead residential building increased. These tended to be more rural locations.

Interpreting this study, Wallace Oates and William Fischel conclude that the benefit-tax view is more appropriate than the capital-tax view when all of the following conditions are met:

- Local property tax revenue is used to fund local services that benefit the property taxpayers. This condition does not hold for school finance in states like California and New Mexico, where new property tax revenue cannot be used to improve local schools, or for local governments in states like Idaho or Michigan where property taxes are so strictly capped that localities depend on transfers from state government to fund local services. It is weakened in states like Texas or New Hampshire between 1999 and 2011 where some of higher-value communities’ revenues are redistributed away.

- The local governments that provide public services and levy property taxes can use “fiscal zoning” to deter free-riding. This condition does not hold in many rural areas with relatively unrestricted land use.

- Sufficient competition and choice exists among local governments in a metropolitan area to create strong incentives to provide good value for money. This condition is weak in most of the South and West, where counties are often more significant providers of local services than municipalities are.[15]

Options for Reform

In thinking about whether property taxes should be capped or eliminated, economists suggest we should contrast them with the alternative revenue sources that would have to replace them (assuming no cuts in spending).

Income taxes are generally more harmful than property taxes because they penalize work, human capital formation, and investment.[16] Local income taxes should distort economic activity more than state income taxes, because it is easier to escape a municipality than a state. In fact, localities may not be able to raise enough revenue if they depend on income taxes alone, because tax competition will drive rates toward zero. Perhaps that means local public services would have to be privatized, but, in that event, private homeowners’ associations are likely to use fee structures remarkably similar to property taxes.

Sales taxes are arguably less harmful than income taxes because they do not directly discourage work, training, and investment. Nevertheless, they do distort consumption decisions and discourage exchange, the foundation of a market economy. Sales taxes are also inefficient because they tax business inputs, discriminating against more complex forms of production. (Value-added taxes avoid this problem but are nearly unknown in the US.) Sales taxes are impractical as a primary municipal revenue source because municipalities vary greatly in terms of their retail development. Replacing property taxes with sales taxes would inevitably mean centralizing fiscal policy in state government, which would dole out revenue to local governments, probably making them less responsive to their residents.

Property taxes are less popular than sales and income taxes because they are more visible.[17] But that might be an advantage of the property tax, since it gives property owners a strong incentive to hold their local governments accountable for performance and provision of value.

Finally, both income and sales taxes are much more volatile and less dependable than property taxes. Income and sales tax revenues go up in good times and down in bad times, while property tax revenues are more consistent. For example, property tax revenues in the US remained nearly constant through the Great Recession.[18]

Unless residents’ property tax burdens are completely disconnected from the public services they receive, economists typically recommend reforming property taxes rather than abolishing them.[19]

Property tax caps have historically proven popular, but they can be badly designed. A study of assessment limits in Georgia found that house prices rise fully to take into account the tax benefit of the assessment limit, worsening affordability for first-time homebuyers and renters.[20] In California, Proposition 13’s assessment limits have locked homeowners into place and created commonplace situations in which neighbors have vastly different property tax burdens. Simply capping property tax rates also doesn’t necessarily do much, because if assessed values rise, the effective property tax burden as a share of income can still rise a lot.

For that reason, a more effective reform might be to cap property tax revenue per household, with an exemption for new growth and perhaps an inflation adjustment, and require a public vote to override the cap. This is essentially how Utah’s Truth in Taxation law works, but it simply requires a public hearing instead of a public vote and does not include an inflation adjustment. A reform like that could hold property tax burdens in check, while still providing an opportunity for local voters to tax themselves more if they want to (and prevent situations where local governments seek state bailouts because they can’t raise enough of their own revenue).

More controversially, one economist has proposed eliminating not just assessment caps, but lags in assessments (requiring annual reassessments) and homestead exemptions that reduce the property tax burden for owner-occupants.[21] The last reform, in particular, is likely to prove politically unpopular, because the primary beneficiaries would be nonresident (and nonvoter!) owners of second homes.

Conclusion

Regardless of where we come out on the question of how to reform property taxes, an understanding of economics and some careful thinking should make our policy choices wiser than they would be if based upon facile slogans and sloppy reasoning.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, property taxes don’t generally hit the poor harder than the rich, and they don’t give more power to the government than other kinds of taxes. They may discourage property owners from making improvements, which a land-value tax could solve, but at the same time, assessing the value of land is a harder problem than assessing the value of real estate.

Abolishing, or drastically capping, property taxes would centralize government at the state level, making local governments less responsive to residents, especially homeowners. The main alternative revenue sources—like income and sales taxes—also tend to cause more economic harm and waste.

To keep property tax burdens reasonable while allowing citizens to have ample freedom to choose a menu of local government services that meets their needs, policymakers could consider reforms that put more power into the hands of local voters to review and veto budget increases, and that refrain from redistributing property tax revenue from some localities to others.

Endnotes

[1] The only state with a significant state-level property tax today, according to the Census Bureau, is Vermont. But figures for Vermont are misleading, because while the state government enacts a statewide education property tax, it allows local governments to adopt “top-up” property tax rates for extra school funds, and the Census Bureau counts these as state rather than local revenues.

[2] Oates, Wallace E. 1969. “The Effects of Property Taxes and Local Public Spending on Property

Values: An Empirical Study of Tax Capitalization and the Tiebout Hypothesis,” Journal of Political

Economy 77 (6): 957–971; Aaron, Henry J. 1975. Who Pays the Property Tax? A New View. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution.

[3] George, Henry. 1912 [1879]. Progress and Poverty, 4th ed. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page & Co.

[4] Albouy, David, Gabriel Ehrlich, and Minchul Shin. 2018. “Metropolitan Land Values,” Review of Economics and Statistics 100 (3): 454-466.

[5] Mieszkowski, Peter, 1972. “The Property Tax: An Excise Tax or a Profits Tax?” Journal of Public

Economics 1 (1): 73–96; Zodrow, George R., and Peter Mieszkowski. 1986. “The New View of the Property Tax: A Reformulation,” Regional Science and Urban Economics 16 (August): 309–327.

[6] Oates, Wallace E., and William A. Fischel. 2016. “Are Local Property Taxes Regressive, Progressive, or What?” National Tax Journal 69 (2): 415–434.

[7] Tiebout, Charles M. 1956. “A Pure Theory of Local Expenditures,” Journal of Political Economy 64 (5): 416-424.

[8] Caplan, Bryan. 2001. “Standing Tiebout on His Head: Tax Capitalization and the Monopoly Power of Local Governments.” Public Choice 108 (1): 101–122.

[9] Fischel, William A. 2001. The Homevoter Hypothesis: How Home Values Influence Local Government Taxation, School Finance, and Land-Use Policies. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

[10] Einstein, Katherine Levine, David M. Glick, and Maxwell Palmer. Neighborhood Defenders: Participatory Politics and America’s Housing Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

[11] Hamilton, Bruce W. 1975. “Zoning and Property Taxation in a System of Local Governments,” Urban Studies 12 (2): 205–211.

[12] Rothwell, Jonathan T., and Douglas S. Massey. 2010. “Density Zoning and Class Segregation in US Metropolitan Areas,” Social Science Quarterly 91 (5): 1123–1143; Bourassa, Steven C., and Wen-Chieh Wu. 2022. “Tiebout Sorting, Zoning, and Property Tax Rates,” Urban Science 6 (1): 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6010013.

[13] Gallagher, Ryan M. 2019. “Restrictive Zoning’s Deleterious Impact on the Local Education Property Tax Base: Evidence from Zoning District Boundaries and Municipal Finances,” National Tax Journal 72 (1): 11–44.

[14] Lutz, Byron. 2015. “Quasi-Experimental Evidence on the Connection between Property Taxes and Residential Capital Investment,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7 (1): 300–330.

[15] Oates and Fischel, “Are Local Property Taxes Regressive,” 415–434.

[16] Bartik, Timothy J. 1992. “The Effects of State and Local Taxes on Economic Development: A Review of Recent Research,” Economic Development Quarterly 6(1): 102–111.

[17] Some empirical evidence from an unpublished NBER working paper suggests that where fewer homeowners pay property taxes through escrow, property tax rates are lower. Cabral, Marika and Caroline Hoxby. 2012. “The Hated Property Tax: Salience, Tax Rates, and Tax Revolts.” NBER Working Paper 18514, https://www.nber.org/papers/w18514.

[18] Alm, James. 2013. “A Convenient Truth: Property Taxes and Revenue Stability,” Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 15 (1): 243–245.

[19] Walczak, Jared. 2024. “Confronting the New Property Tax Revolt,” Tax Foundation (November), https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/state/property-tax-relief-reform-options/.

[20] Horton, Emily, Cameron LaPoint, Byron Lutz, Nathan Seegert, and Jared Walczak. 2024. “Property Tax Policy and Housing Affordability,” National Tax Journal 77 (4): 861–901.

[21] Ihlanfeldt, Keith R. 2013. “The Property Tax Is a Bad Tax, but It Need Not Be,” Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 15 (1): 256–259.