What determines the price of a stock, bond, or other income-producing asset? Interest rates play a larger role than most people recognize, and the political fight over interest rates is going to be one of the central themes of the next decade.

In describing why that’s true, it’s useful to start with “this one weird trick”: consols. You have likely never heard of consols, but after reading this, I hope you never forget them. Consols (a flippant shortening of “consolidated annuities”) were introduced in 1751 by the British government as a type of government bond, an instrument that pays a fixed interest indefinitely and never “matures.”

Now, most bonds have three associated parameters:

- the principal (the par value of the bond, also the amount borrowed by the government)

- the coupon rate, or rate of return paid to the bondholder

- the date of maturity, when the bond can be exchanged for its par value

For example, a 30-year, one-thousand-dollar bond with a 4 percent coupon rate would be purchased “new” for $1,000, would pay $40 per year, and in thirty years could be cashed in for the original par amount, $1,000.

Let’s suppose the risk of default, or failure to repay, is negligible. That means the bond is pretty safe, right? Well, if the buyer intends to hold the bond to maturity, it is indeed safe: in thirty years, that bond will definitely be worth $1,000, and that would even be its price if someone were to buy it from the holder the day, or week, before the maturity date.

The wrinkle is that it is possible to buy or sell the bond in the period between when it was issued and just before it matures and is cashed in. What is its value during that period, say a year after issuance, and 29 years before maturity? Interestingly, the answer depends on another factor:

4. the prevailing interest rate, at the moment of the proposed sale, for other debt instruments of the same risk class

To see why this matters, suppose you have owned the $1,000 bond for a year, you just cashed in your $40 “coupon” for the first year, and now you are thinking you will unload the bond because you need the money to buy something. You notice interest rates have gone up, from 4 percent to 5 percent, but hey, this is a $1,000 bond, right?

Not so fast. Since interest rates are now 5 percent, the potential buyer will only buy your bond if she can expect a 5 percent return. Your bond pays $40 per year, which is 5 percent of $800, not $1,000 (again, ignoring proximity to maturity). The buyer is thus indifferent between buying a new bond for $1,000 — earning 5 percent directly — or buying your bond for $800 and getting only $40. But that means you took a loss of $200: bonds are not so safe, after all.

This is where consols come in as an interesting simplification, because treating a bond as if it had no maturity date can be a convenient approximation for bonds with maturity dates that are far off. Consols were bonds that had a par value, and a fixed coupon rate, but no maturity date — they were perpetual, though in the case of England the government retained the right to “call” or redeem the bonds at its discretion.

Created by Chancellor of the Exchequer Henry Pelham in 1750, they were designed to consolidate England’s crushing high-interest war debts. The government combined various existing debts into a single, lower-interest bond at 3 percent (later 4 percent), starting the following year.

The purpose of consols was twofold: (a) to stabilize British public finances by refinancing expensive short-term obligations into long-term, manageable liabilities; and (b) to create a liquid, tradable instrument that could underpin a reliable domestic capital market. (As I have pointed out before, a paper currency such as dollars or pounds can plausibly be thought of as a perpetual zero-coupon bond; consols were likewise a means of assuring liquidity for the financial system.) Ultimately, the outstanding consols were finally called and redeemed in 2014 and 2015, ending their 250-plus year run.

As noted above, the most common consols paid 3 percent or 4 percent, and had a £100 face value. Of course, they rarely traded at £100, since interest rates were rarely at exactly 3 percent or 4 percent, but they had relatively stable value as portfolio assets because the English government had incentives to maintain steady interest rates.

Okay, so then what is the “trick”? We know that the value of a bond is equal to an amount that just matches the coupon rate to the prevailing interest rate, as in the previous example. A consol is a promise to pay that coupon rate forever; what is that promise worth? The trick is that the answer to that complicated question is surprisingly simple. Let x be the yearly coupon rate, and let r be the prevailing interest rate on other assets. Then the value or price P of a consol is:

Proving this requires taking the limit of the infinite series of sums of discounted present values of future payments, but it’s already been proved, and we can just use the result: the price of a stream of annual payments is equal to the annual payment divided by the interest rate. End of story. It’s amazing!

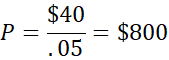

Notice that we already saw an example: how much was the $1,000 and 4 percent bond worth after interest rates went to 5 percent? Since 29 years until maturity is “like” forever, we just take the annual coupon payment and divide by the new interest rate:

(The “correct” answer, using a more complex formula that accounts for the $1,000 value of the mature bond 29 years from now, is a little less than $850, so it’s a decent approximation to treat this bond as a consol!)

If you have not seen this simple formula before, it is going to change your life; I use it almost every day. If there is a stream of payments, or of value of some kind, that goes multiple periods into the future, you can make a quick back-of-the envelope guess at how much it is worth.

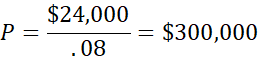

You are considering buying a house, to rent out on an annual lease of $24,000, or $2,000 a month. You can borrow money at 8 percent, so that’s your interest rate. What is that stream of payments worth?

Of course, 30 years is not forever, but the correct answer using Excel (PV{r,n,X}) is $270,000. You can use the consol formula as an upper bound, and figure it in a few seconds. If the house costs less than $300,000, the investment might work out.

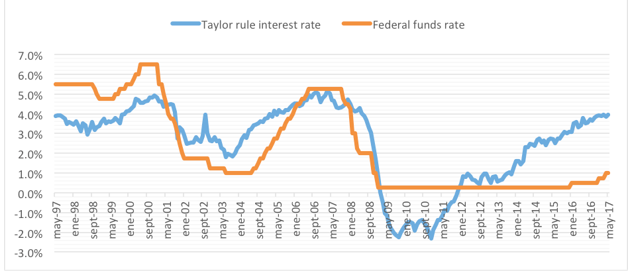

The reason I have spent all this time developing the formula for a perpetual annuity is that it illustrates the importance of interest rates in valuing assets. According to most observers, the US Federal Reserve has often kept the “federal funds rate,” the benchmark interest on short-term loans, below — and sometimes well below — the so-called “Taylor Rule” rate. What that means is that rates were artificially low in a way that artificially inflated asset values for much of the past three decades.

To see the magnitude of this effect, consider the following table. Suppose a firm expects to make net profits of $1,000 per year for the foreseeable future. How much is the firm worth? We can apply our formula: if interest rates are 20 percent, then the firm is worth $5,000, nothing to write home about. But if rates are lower, the firm is worth substantially more: if rates are 2 percent, the value of the firm is $50,000, ten times as large as it was with a 20 percent rate. Notice that there has been no change in the firm, what it does, or its profit, which is $1,000 per year.

Table 1: The Value of a Firm with Profits of $1,000 per Year

| $1,000 | 20% | $5,000 |

| $1,000 | 15% | $6,667 |

| $1,000 | 10% | $10,000 |

| $1,000 | 5% | $20,000 |

| $1,000 | 2% | $50,000 |

| $1,000 | 1% | $100,000 |

| $1,000 | 0.50% | $200,000 |

| $1,000 | 0.10% | $1,000,000 |

| $1,000 | 0.001% | $100,000,000 |

As interest rates approach zero, the value of the firm explodes. At a rate of 1/10 of a percent, the firm is worth a tidy million dollars; at 1/1000 of a percent, the firm is worth $100 million, a fortune.

The important thing to note is that this “interest rates near zero” condition is not hypothetical. The US Federal Reserve has often set “Federal Funds” rates below the Taylor Rule, and between 2009 and 2016 those rates were indistinguishable from zero. This actually happened.

Figure 1: The Taylor Rule and the Fed Funds rate

Using the “one weird trick” formula, then, we are able to illustrate the dependence of asset prices on interest rates in a way that makes things disturbingly clear. One way firms can raise their stock prices is make better, cheaper products and increase their annual profits. Another way, the modern American way, is to let annual profits stagnate, but use cronyist techniques to petition government officials for artificially low interest rates.

US industry has grown dependent, even addicted, to the destructive drug of artificially low interest rates. Either the US continues that destructive policy, as a way of propping up zombie businesses, or else burgeoning deficits cause interest rates to shoot up and businesses go bankrupt in waves. Either of the two alternatives is frightening. But now you understand the problem, because you have learned that one weird trick.